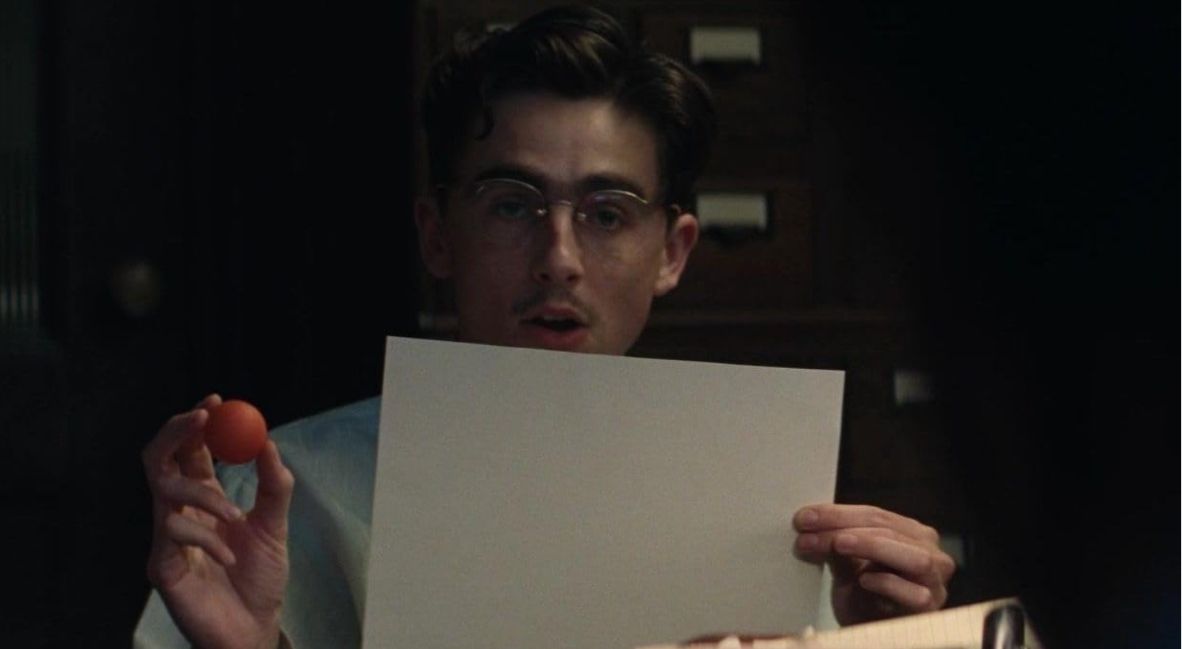

There are certain stereotypes of Jewish masculinity that are supposed to come with the territory of a movie like Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme. In the film, Timothée Chalamet stars as Marty Mauser, a young Jewish man living in a post-war Lower East Side Manhattan. Marty is supposed to be physically meek but intellectual to a fault; his mother is supposed to rule his life, and if not her, his wife, both overbearing and under supportive at once; and he’s supposed to be overcompensating for all of this with miserly social climbing and conniving amongst old-money white gentiles to prove a sort of masculine capitalist-patriotism.

In many ways, this is how Marty Supreme presents its characters. It fits the bill for countless Hollywood Jewish characters created and portrayed from the turn of the 20th century through today. But Marty is a much, much more nuanced character and portrayal of Jewish masculinity than that surface-level description would suggest. Marty Supreme masterfully bucks the typical notions of Jewish masculinity and gender altogether.

Those stereotypes don’t come from nowhere, of course. Jewish writers—writers of all kinds of backgrounds—have turned to self-deprecatory humor to ease the consciousness of the white upper classes. As the idea has always gone, if we can make fun of ourselves, then we can become more palatable and eventually acceptable amongst them.

Jewish masculinity has an ancient history of self-mythologizing.

The Jewish self-assessment of masculinity is ancient. Traditional texts regularly depict Jewish men as “effeminate” compared to other men. They study all day and have no physical prowess. Rabbis in the 5th and 6th centuries enshrined it in the Talmud, describing Jewish men with “strength only fit for study, and beauty only fit for a woman.” When your ancestors have been calling you weak, skinny, and ugly for a millennium and a half, it starts to sink in and become a self-myth.

To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with men who possess any of the qualities that are so often attributed to Jewish men. Neither would there be anything wrong if Jewish masculinity was truly based in things like study and low beauty standards.

There is an entire book of Jewish ethics, Pirkei Avot, compiled in the 3rd century and still central to Jewish ethical formation and practice today. It’s dedicated to themes of justice through peace, wisdom through the wisdom of others, strength through conquering one’s impulses to anger, and honor through love for every living being. The well of sources on the formation of Jewish, especially American Ashkenazi Jewish masculinity, runs deep.

Marty Mauser fulfills the Jewish masculinity stereotypes for his place and time.

Formulating a character like Marty Mauser in Marty Supreme around even the most basic stereotypes for Jewish men isn’t unreasonable screenwriting on its own. It’s a familiar character archetype in a familiar kind of world, whether you’re a Jewish viewer or not.

Marty lives in the very Jewish Lower East Side of New York, where Yiddish storefronts and newspapers are everywhere, and all his neighbors are Jews. But he doesn’t exist in a purely Jewish bubble, the way that he so easily could. Marty has one best friend, Wally (Tyler the Creator), who is Black, and another, Dion (Luke Manley), who is seemingly a white gentile, or at least more assimilated than the Jewish star-wearing Marty is. This is the first hint that Marty Supreme is doing something different.

Wally and Dion aren’t just token non-Jewish characters to add diversity to the movie. They are integral parts of Marty’s everyday life and sense of self. He is who he is as a person because of these friendships, just as much so as his friendship with Jewish Holocaust survivor and table tennis rival Béla Kletzki (Géza Röhrig). They’re markedly different than his relationships with Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow) and Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary), the old-money actress and business titan whom Marty latches onto as his potential ticket to a higher social class.

Instead of “Jewish guilt,” Marty Supreme employs outright shame to mold its gender politics.

Yes, Marty’s relationships with just about everyone in Marty Supreme are transactional, including his closest friends. But the difference is that with his friends, you can tell he loves them, and you know that he feels guilty. You sense that he wants to repay them for the kindnesses they’ve done him and the ways he’s done them wrong.

It’s not a nagging “Jewish guilt,” where some outside force, like his mother or girlfriend, is making him feel bad for what he does. Marty’s mother (Fran Drescher) is where he gets his scheming wits from in the first place. Instead, Marty has a genuine sense of shame. It comes over him from time to time among his dear ones, the similarly downtrodden, but he never reciprocates it towards the rich snobs he half-heartedly cowtows to out of obligation.

Typical effeminate Jewish masculinity would dictate that Marty be unathletic, smart and shrewd, not virile, and, especially during the post-war period, stateless—meaning, the United States as a nation does not belong to him as a Jew, and neither does the recently established “Jewish State” in Israel, because he is an American. (Israel is never mentioned in Marty Supreme whatsoever, but it is inately part of the historical context of the time period).

Marty is ashamed of these circumstances, driving him to overcome them, but being ashamed of how others perceive him is distinct from his moral value of feeling shame for how his actions impact others. Shame may be classifiable as an effeminate trait, but it’s not the typical trait ascribed to male Jewish protagonists. Repentance is usually depicted as being encouraged by external sources rather than as an inherent value that such characters already possess.

Marty Supreme asks: Are they stereotypes, or are they insurmountable facts?

Everything that Marty does from the beginning to the end of Marty Supreme is a direct challenge to those preconceptions of Jewish masculinity. He is a global top performer in his sport, table tennis, and he has very little business and interpersonal acumen despite plenty of great ideas and connections. The movie opens up with one of the year’s hottest meetups and a hilarious display of just how virile Marty really is. And, his pursuit of both table tennis glory and a relationship with Kay Stone is designed to prove that he is, indeed, an all-American type of guy.

The irony is that his pursuit of a “new” kind of Jewish masculinity, in so many ways, only further proves the myth. Sure, he’s a professional athlete, but in one of the seemingly least athletic sports imaginable. He’s a skinny kid who gets beaten up easily and often, despite his unparalleled bloat and bluster.

The reality is, even if Marty could turn table tennis into an American sensation and plant himself on a box of Wheaties, people like Rockwell would simply never accept him or any Jewish kids like him as his equal in society. The film begs the question: Is Marty just embodying stereotypes, or would he have to give up his Jewishness entirely to actually climb the social ladder? And if he took off his necklace and changed his name, would that really change who he is inside?

Rachel enjoys equally complicated relationships with gender as Marty does.

Somebody who is Marty’s complete equal, in both of their eyes, is his childhood best friend and not-so-secret fling, Rachel (Odessa A’zion). On her own, Rachel is an incredible character. She is smarter and more talented in ways than Marty, but just as prone to social and business disasters as he is. Rachel makes her own decisions about how to help herself and support Marty, regardless of how he would feel about them. And, she is just as charismatic, attractive, and thrilling to watch as Marty.

Marty isn’t emasculated by Rachel, even when she is as smart, daring, and scheming as he is. He does diminish her to “nothing” in the vanity of his own singular glory, but it’s not personal; this is his defense mechanism with everyone he cares about to keep them at a distance while he’s on his mission. When his mission is complete, Rachel is the first thing on his mind, and she becomes the mission. Not in a patronizing way. They both accept one another’s drive and the flaws that come with the territory, no matter what. Their respect is completely mutual, beneath the bluster and missteps.

Marty Supreme isn’t attempting to disprove anything about how Jewish masculinity is formed, Marty’s self-identity within it, or how he strives to acquire a “new” Jewish masculinity in a post-war New York. He fulfills each expectation to great effect in a fantastically compelling movie. What makes it compelling, rather than trite, is the fact that Marty Supreme examines that masculinity so deeply.

Marty’s quest for a “new” Jewish masculinity is deeply authentic and complicated.

Rather than merely portraying a story about a walking stereotype, Marty’s journey through the movie is about demonstrating how he is hurt by traditional Jewish masculinity. His perceived weakness makes him a joke to the upper class he is trying to reach.

The movie is also about how his striving to form a “new” masculinity is just as much a trap as the “old” one. He repeatedly puts his and his friends’ bodies in harm’s way as he goes too far in his quest for assimilation and social mobility.

And yet, Marty Supreme is kind to that masculinity. It uplifts the parts that deserve praise, like his unflappable spirit and his tenacity in his sport. But it also shoots down the parts that hurt him, like his stubbornness and selfishness, and encourages him to embrace the “effeminate” qualities that make him great, too, like his shame, his caring, and his intellect.

Marty Supreme is neither judging nor celebrating the trials of masculinity; it’s seeking something deeper.

Marty Supreme is a wonderfully nuanced exploration of why the traditional notion of Jewish masculinity has stuck for so many centuries, how Jews in the mid-century attempted to evolve that perception and definition, why they did so, and how it resulted.

The fact that Timothée Chalamet is himself a young Jewish man navigating these same concepts of Jewish masculinity before our eyes in the media every day is not lost, either, on how perfect his casting is for this character.

The movie isn’t a judgment piece about why or whether these constructions of manliness are inherently good or bad, but rather, it’s a treatise on simply understanding it all and using that understanding to help ourselves ask, “Where do we go from here?”

Marty Supreme is in theaters now.