This article contains spoilers for volumes 24 and 25 of the My Hero Academia manga

Villains are a key element to most of the best stories and the great villains often come with a small kernel of light in their story that links them to the audience. This kernel is there to build up a bit of sympathy for the villain. But the best villains are the ones who use that sympathy against the audience to showcase how they are irredeemably warped. The villains’ writers can call for us to sympathize with a character that has been pushed by circumstances but to make us feel that sympathy is much harder. More than that, though, there is a fine line to walk between making us sympathize and outright defending the indefensible. So how do you build a villain that connects to the audience and then hits them emotionally while still keeping their evil at the center? Well, you build Tomura Shigaraki.

Shigaraki is the leader of the League of Villains in Kohei Horikoshi’s My Hero Academia. In the series, the characters live in a world of heroes, one where individuals can be born with special abilities known as “quirks.” The key to Horikoshi’s compelling worldbuilding is that he explores the social and cultural implications of superpowers suddenly emerging in the populations mere decades ago. While some people seem to have ideal quirks for heroism, others are dismissed as having quirks unsuitable for hero work. Even more, some quirks have their users labeled as villains from the moment the quirk awakens. These “villain” quirks are not a prophecy, though. While we’ve only skimmed the surface of this in the series, it serves as an entry point for readers to find an ounce of compassion for villains, even those with absolutely devastating abilities.

Is it really your fault if the world is stacked against you?

If your hero is always 100 percent right and your villain is always wrong, then there is little room for nuance. Traditionally in pop culture, villain origins aim to make the reader or viewer care for the people who will become monsters. These narratives exist to draw out compassion and to complicate the story of good vs. evil. This is fun for a while, but it can quickly grow stale. This is especially evident in the current age of screen adaptations of comic book villains. Take 2019’s Joker for example, which aims to paint the titular villain as a sympathetic victim turned bad by a flawed mental health system and not the chaotic evil he has always been. On the other side of the coin, trying to make a villain empathetic can easily cross into the territory of absolving the villain of their atrocities. I mean, when Joker takes a life, we’re supposed to see how he was pushed to it. We’re supposed to see the broken system as evil and and him as simply a product of evil.

What these narratives fail to take into account is human choices. That’s what separates villains and heroes. They both are often born from tragedy but one chooses to channel it into good and the other into evil. Both heroes and villains choose lives of violence that ordinary people do everything they can to avoid. The difference between a hero and a villain is why they choose to live that life. The tragedy of a villain is that they chose to become a villain. Whatever their circumstances, there is always a moment of choice. While choices aren’t always available for humans in the real world, in the world of My Hero Academia, as with most fiction, choice is key. While society may impact your chances of getting into a top hero school, the road is there for the characters to take.

As we’ve seen in My Hero Academia: Vigilantes, those who use their powers outside the system do so to push against society’s expectations of them, but still aspire to heroism and doing good. Villains on the other hand hurt others, seek power, and – in Shigaraki’s case – look to break the world down to bits and rebuild it in his own image. In fiction, there must be a line between compassion and absolution. While the most compelling narratives are not always black and white, telling those stories of imperfect heroes requires the author to allow for gray areas while still drawing clear lines for morlaity. The hero may not always be able to do the right thing, but there is a right thing to do.

The importance of choice has already been a major point in My Hero Academia. While Shigaraki’s quirk can be seen as villainous, Horikoshi has given us examples of other “villain” quirks that have been channeled towards good. He explored this most explicitly in the 1A vs 1B arc, which featured the mind-controller Shinzo coming into his own as a hero. He overcame the expectation that his mind control quirk was something that could only deal harm and, in fact, used his “villainous” quirk that saves the main character, Deku, from himself.

Horikoshi understands the important of balance and when he presents Shigaraki’s origin story to the audience, we see the villain’s tragedy. In fact, the author does this for all of his villains in the League. But Horikoshi never loses sight of the agency of evil. Over the course of volumes 24 and 25 of the manga, Horikoshi unwinds the tale of his villain’s life. A grandchild of one of the holders of One For All, the power given to the series’ protagonist, he looks towards a future of heroism. But, his father abuses the heroism out of him. Through witnessed verbal and emotional abuse, Horikoshi builds Shigaraki’s sadness, isolates him, and disconnects him from the lineage of One For All. When we see the physical abuse, it gets at the depth of the anger Shigaraki’s father had towards heroes and how he passed that anger down to his child through violence.

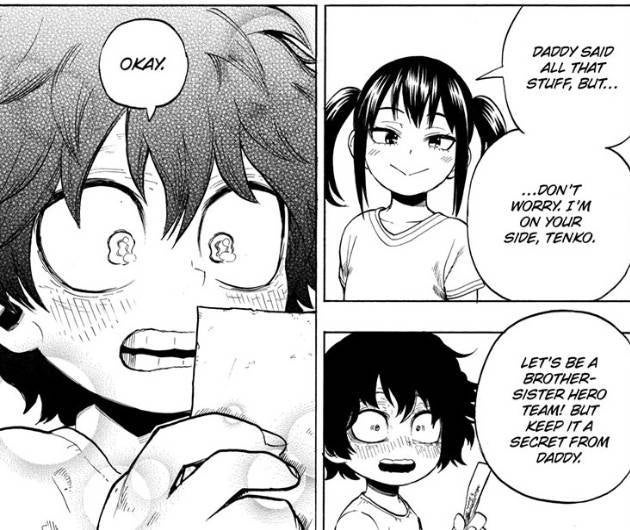

Initially, as you’re working through the opening chapters of Shigaraki’s origins you want to hug him. You want to save this child. Emotionally, Horikoshi exploits your protective instincts, weaving your sympathy into his story. Horikoshi pushes this by illustrating young Shigaraki in a similar style to Deku. A fan of parallels throughout the series, there are moments of excitement for heroes replicated in Shigaraki. Horikoshi pulls you into Shigaraki’s life and then he rips you apart.

Spurred by fear and anger, young Shigaraki’s powers awaken, destroying his pet, his sister, and his mother. That moment of pain and grief deepens your connection to him. This isn’t his fault. His quirk isn’t in his control. And for a moment, you equate him to Eri, another character in the series who kills her parents because of her quirk manifesting. While she can’t control it, we get to see her remorse, her fear, and we know this isn’t her choice. That said, as Shigaraki’s power escalates he begins to understand what it can do. In the span a of few panels, he’s nearly killed his entire family. And while there is initially guilt, it disappears the moment his father walks outside.

Told through powerful narration, Shigaraki unequivocally states his intention: patricide. While the deaths of his mother, sister, and beloved pet are accidents, the murder of his father is anything but. In fact, the catharsis that Shigaraki feels in the moment of killing his own father fuels him to seek out more death and to destroy more, an itch he can’t scratch. The catharsis of murder is what drives him to choose villainy. The audience sees the impact of All for One – the series’ lead villain that hovers over every volume like a specter of evil – on the young Shigaraki after he saves the budding villain from the streets. While everyone ignores an abandoned child, All For One opens his home to him, names him, and provides guidance. While that guidance is built on nurturing his quirk for his own use, it is guidance nonetheless, using the child’s rage and anger to fuel his development into the villain we see in the current timeline.

However, Horikoshi is careful not to absolve Shigaraki of his deeds. Shigaraki’s first kills were sheer accident and the abuse he suffered would’ve emotionally scarred anyone, but Shigaraki is the one who finally decided to keep the blood flowing (metaphorically, because when he kills there is no blood). While his quirk awakening is traumatic, Shigaraki’s narration describes the relief he feels from killing. While the guilt is earth-shattering at first, it almost immediately gives way to ecstasy.

This narrative of abuse and violent retaliation is a masterclass in building a villain through both compassion and evil. Additionally, as we see the choices Shigaraki makes afterward, we understand his agency in choosing murder repeatedly. While All For One nurtures the anger and rage inside him, it is Shigaraki who acts on it. That said, Horikoshi also grounds Shigaraki’s evil with his guilt. The hands he wears are not for decoration. Instead, they’re the hands of his family, his first victims. They remind him of his deeds, the small guilt he feels, until he finally throws them off to emerge with more rage, more power, and be unrestrained by any semblance of life before his power.

Now in Chapter 286, Horikoshi has positioned Shigaraki as a nearly world-ending level villain. Not only does everything he touch turn to dust, but once his powers are enhanced by the scientist who kept All For One alive, even the debris caused by his quirk will kill. There is no escaping the death that Shigaraki brings and because of this, we’re given the highest stakes this series has ever seen.

Shigaraki is devastation and destruction incarnate, and he chose this path. From tragedy, he chose violence and villainy. All For One, but he always chose to let them lead him towards evil. And that, the clear agency in evil, is how you build a compelling villain. You can love a villain, you can feel for them, and the author can lean into that. But, when they are evil and choose that evil, that is where the empathy we have is balanced with our fear of the character. The elements in Shigaraki’s narrative bring out the compassion in the reader. In fiction, the villains who choose evil after tragedy can present a deeper fight for morality and hope than someone who falls into villainy by happenstance.

Compassion for evil doesn’t need to be out of bounds, but multifaceted villains can and should be kept evil. Regardless of their motivations, a writer who understands how to build a villain by tethering them to their evil deeds instead of apologizing for them is what separates compelling narratives from problematic ones.