It is no secret that the anime industry and community have an anti-Blackness problem. They are not the only ones; anti-blackness is literally everywhere. Previously, I wrote about the harsh reality of being a Black anime and manga fan and the truth of anti-blackness in the industry. The piece reflected a broader global issue that appears in the media we love and came from a place of frustration, pain, adoration, and hope.

Frustration and pain because anti-Blackness is exhausting and disheartening as a fan of anime to see people who look like you being reduced to a stereotype. Whether it is on a micro or macro aggressive level.

Adoration, because as much as anime has its problems and history with anti-blackness, like nearly anything else in this world, that does not besmirch the entire medium for me as a fan. However, while Black representation in anime is moving in the right direction, more work still needs to be done.

I had hoped that since naming and discussing the problem, more change might occur. Although I received a lot of negativity and hate from the article, that paled in comparison to the number of thoughtful conversations and validations other fans like me felt after reading it.

I am pleased to say that anti-Blackness and Black representation in anime are improving. Over time, anime and manga creators have made meaningful steps toward including more Black characters with intention and nuance. Some great examples can be seen in recent popular series like Gachiakuta, Trigun Stampede, and Lazarus, as well as anime-adjacent series such as Castlevania: Nocturne.

From beautifully and intentionally designed characters to the inclusion of more Black voice actors, Black-led projects, and Black-owned animation studios, the landscape is shifting in the right direction for the medium and the animation that is inspired by it. Although it is thrilling to see this progress, the work is not yet over. Here’s a look at how far we’ve come and where we still need to go.

How Far We’ve Come

For years, Black representation in anime and manga was either completely non-existent, portrayed ambiguously, otherized, whitewashed, or displayed as offensive racist stereotypes. Many of the racist and stereotypical features of Black characters in anime were heavily inspired by Western media’s racist caricatures of the time. Thankfully, recent years have shown signs of real progress in creating and designing Black characters with intention and creative integrity.

Intentional Black Character Designs

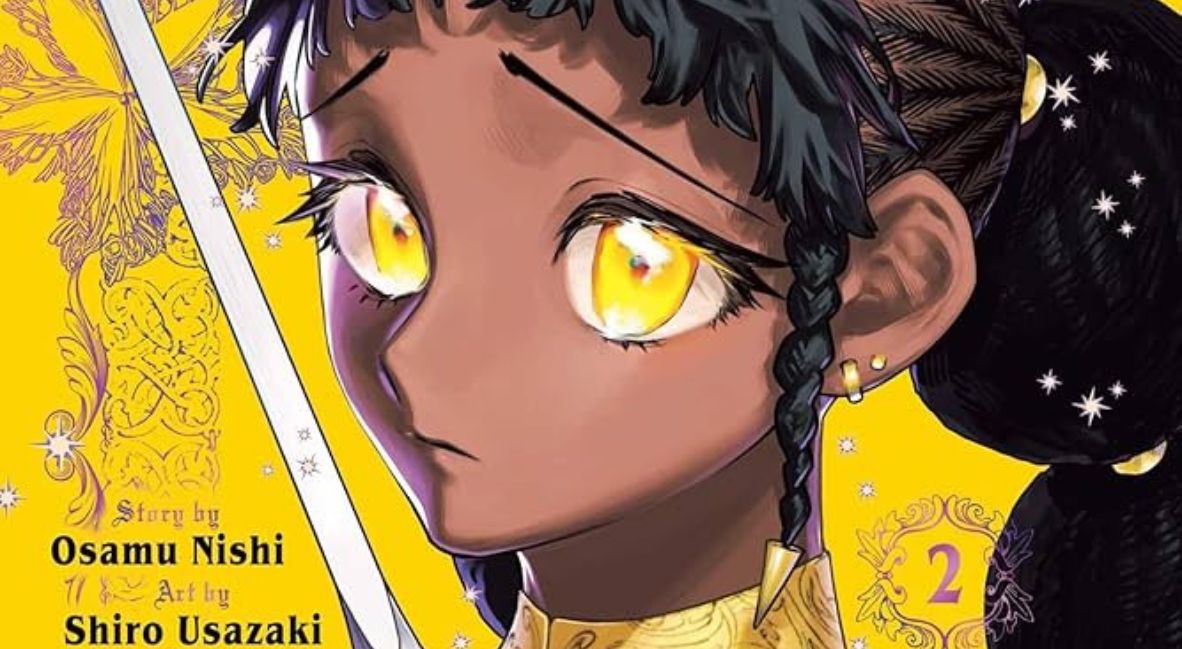

We are starting to see more Black character designs with an intention that reflects more care, authenticity, and integrity, instead of being modeled after racist caricatures, ambiguity, and or degrading stereotypes. Some notable recent examples across anime and manga series include characters such as Desscaras from Ichi the Witch, Jessica from Trigun Stargaze, Doug from Lazarus, and Jabber, Corvus, and Semiu from Gachiakuta.

The designs for these characters stand out because they are intentionally meant to represent Black and or African-descent characters and to reflect Black people. For example, Desscaras’ design features lighter-toned palms, afro-textured hair, and braids rooted in Black culture. The same can be said for Jessica’s character design in Trigun Stargaze.

Another example of deliberate Black representation is in Gachiakuta. Characters like Jabber, Corvus, and Semiu further demonstrate this shift by featuring diverse skin tones, facial features, body types, and hairstyles that highlight the vast array of Black features. Similarly, Doug in Lazarus is a Black man whose design and features reflect a more grounded portrayal while avoiding any stereotypical elements.

The creators of these series are signaling something important by incorporating this level of detail into their characters. They say their characters are not meant to be otherized or interpreted as racially ambiguous or as tan. Instead, these characters are intentionally and recognizably Black. The increasing number of anime and manga creators shifting their designs shows meaningful progress in how Blackness should be represented, not as a caricature or stereotype, but as an identity, culture, and lived experience.

More Series Centering Black Characters and Stories

Another sign of progress is the centering of Black characters and their cultures in stories that exist within and adjacent to the anime industry. It is essential to mention that anime, by definition, is animation produced in Japan. Same as how “manga” refers to Japanese comics. The distinction between these media matters not just to show respect for Japan’s cultural ownership of anime and manga, but also to clarify that representation in Japanese anime carries a different cultural weight.

When Japanese anime depict Black characters, they shape how Blackness is understood and perceived within Japanese media. However, anime-inspired and hybrid productions still play a meaningful role in this discussion, particularly when they collaborate with Japanese studios directly rather than merely borrowing from the medium’s aesthetics.

Castlevania: Nocturne is an excellent example of this. The series is a Western-produced animated series that draws heavily from Japanese anime visuals and storytelling structures. Additionally, it is worth noting how Castlevania: Nocturne boldly centers and depicts its Black characters, Annette and Drolta.

Both characters’ arcs and cultures become central to the main plot of Castlevania: Nocturne Season 2, rather than being relegated to a supporting role or one-off characters. Both Annette’s and Drolta’s backgrounds and cultures are intentionally included in the plot and play a role in the story.

Another significant example of centering Black characters, and one that is also a unique US-Japanese co-production, is Cannon Busters. LeSean Thomas created Canon Busters as a comic series and later premiered it as a Netflix Original Anime series in 2019. Thomas moved to Japan to collaborate with local creators, leading him to partner with the Japanese studio Satelight to produce the anime Cannon Busters.

The series centers on predominantly Black and other people of color as the main characters, set in a western-futuristic action-adventure. Although the series received mixed reviews and insufficient viewership to justify a second season, it should still be hailed as a great addition to the anime world, offering a fresh, original story with a predominantly Black and mixed cast.

Cannon Busters is also uniquely positioned in this conversation about representation because it is not just a series with anime aesthetics. Instead, it is a genuine cross-cultural partnership that demonstrates what can happen when Black and Japanese creators work together.

Additionally, it was recently announced that Yoiko Fujimi’s manga series Half is More will be released in English. The series focuses on two Black-French and Japanese biracial siblings and explores their experiences navigating identity and belonging as Black people living in Japan.

Yoiko Fujimi’s manga is unique in that it is a Japanese work that explores the Black experience and biracial identity. Half is More is a vital step toward expanding how Black people and stories are represented.

More Black Lead Anime Projects

In addition to more anime centering on Black characters, we are also getting more anime projects led by Black creators. Viola Davis and her husband, Julius Tennon, through their production company JuVee Productions, announced in 2024 a partnership with Black-owned media company N LITE to produce the Afro-anime fantasy film Mfinda. Mfinda: A Journey Between Worlds is set to release in 2026 and follows a young Congolese girl who is transported to a forest filled with spirits and magic.

Another Black-led project in the works is Megan Thee Stallion’s original anime, currently being developed with The Boondocks producer Carl Jones. Announced in 2025, the anime is still in development and is set to stream on Amazon Prime Video.

Although there are not many details about the anime’s premise and characters at this time, the artist has shared on her social media that the series reflects her deep love for anime and promises to be unique, high-energy, and full of character development.

Both projects highlight once again how more Black creatives are using their platforms and industry knowledge to produce original anime that reflect their communities, and how this creates more opportunities for Black and other people of color to enter the anime industry and tell stories inspired by their culture and experiences. This also helps improve Black representation in anime, not just on-screen but also behind the scenes.

Where We Still Need to Go

Despite the creative progress and meaningful inclusion of more Black talent behind the scenes, representation often still falters or is met with resistance and hate. While Black characters are increasingly becoming designed with more intention and care, the response to that progress is not always positive, nor is it always supported by the anime industry and community surrounding it.

The disconnect is apparent. Black people and their culture may be celebrated or at least tolerated as an aesthetic, but they are frequently challenged, erased, or outright rejected when real-world accountability is needed.

At the center of these issues, there are two paths forward that are different but equally essential. The first is accountability within the Japanese anime and manga industries.

When Japanese creators include Black characters in their work, those characters should be held to a higher standard than stereotypes or racial ambiguity. Designing characters with intent and respect for their race, culture, and identity should not be considered optional; it should be an integral part of conscientious storytelling.

The second path forward is continued growth, support, and collaboration with Black-led anime-inspired and or anime projects. Black creators building studios and production companies, to tell their own stories, and make their own anime or even collaborating with Japanese creators and studios does not solve the issue of anti-blackness in anime entirely. Instead it is a step in the right direction to help improve representation and help reshape the medium to be more inclusive.

Black-led anime projects and collaborations with Japanese creators are great progress, but they are still isolated victories. Although they can help ensure Black stories and characters are not limited to external interpretation or conditional acceptance, anti-blackness in anime is an industry wide issue, that can not be resolved by individual projects.

These paths are not in conflict with one another; rather, they should be explored together. Wanting anime to treat Black stories or any other race’s representation with respect and care does not remove the need for Black-led projects or collaborations. Similarly, celebrating Black creators does not absolve the anime industry of its responsibility to do better when it chooses to depict Black people or any other race, for that matter.

While these solutions are easier to talk about than to implement in the real world, resistance to these paths often arises when responsibilities are avoided or overlooked. Resistance shows up in casting decisions, in the treatment of Black talent, and in how Black fans are bullied in fandom communities. Progress in representation does not mean everything is fixed; there is still more work to do to make the anime industry, medium, and community more inclusive, safe, and respectful.

Intentional Representation Meets Industry Resistance

Gachiakuta mangaka Kei Urana has been very open and intentional about designing characters meant to represent people of Black and African descent. Urana’s intentional work is part of what has made the series resonate with so many Black fans and has earned praise as a step forward for Black representation in anime and manga.

Although Urana’s intentions for representation are clear, that does not mean the industry shares her sentiments or her dedication to inclusion. That much became clear when casting for the Gachiakuta stage play adaptation, and the subsequent backlash ensued after it was revealed that no Black actors were cast in the Black character roles.

Previously, Urana publicly stated on social media that they specifically asked that performers of African descent portray Corvus and Semiu. The producers of the stage play claimed that it would be difficult to find Black actors who spoke fluent Japanese and had the experience to portray the role well.

The idea that there are no Black actors and performers who speak and perform in Japanese fluently is just not true. Several Black actors and idols in Japan are active in the entertainment industry. For example, Joel Shohei, a Black actor, portrayed Miguel in the Jujutsu Kaisen stage play.

Crystal Kay Williams is a popular Black and South Korean Japanese-born singer, songwriter, and actress who has been active in Japan. Karim Ryuta Nesmith is a Japanese and African American singer, dancer, and actor native to Japan.

The point is that Japan is home to Black actors, singers, dancers, and performers with professional stage experience, many of whom are more than qualified to audition for these roles. So, the issue here is not a lack of Black talent in Japan, but a lack of willingness to be inclusive.

The stage plays casting underscores a recurrent industry problem: Blackness is often celebrated as an aesthetic or style, but opposed when it requires structural effort, access, or the presence of real Black people.

Reception and Treatment of Black Representation in the Anime Community and Industry

While representation has improved within anime itself, the reception of Black representation, particularly when it involves real people or explicit racial acknowledgment, often reveals deep resistance from segments of the fandom.

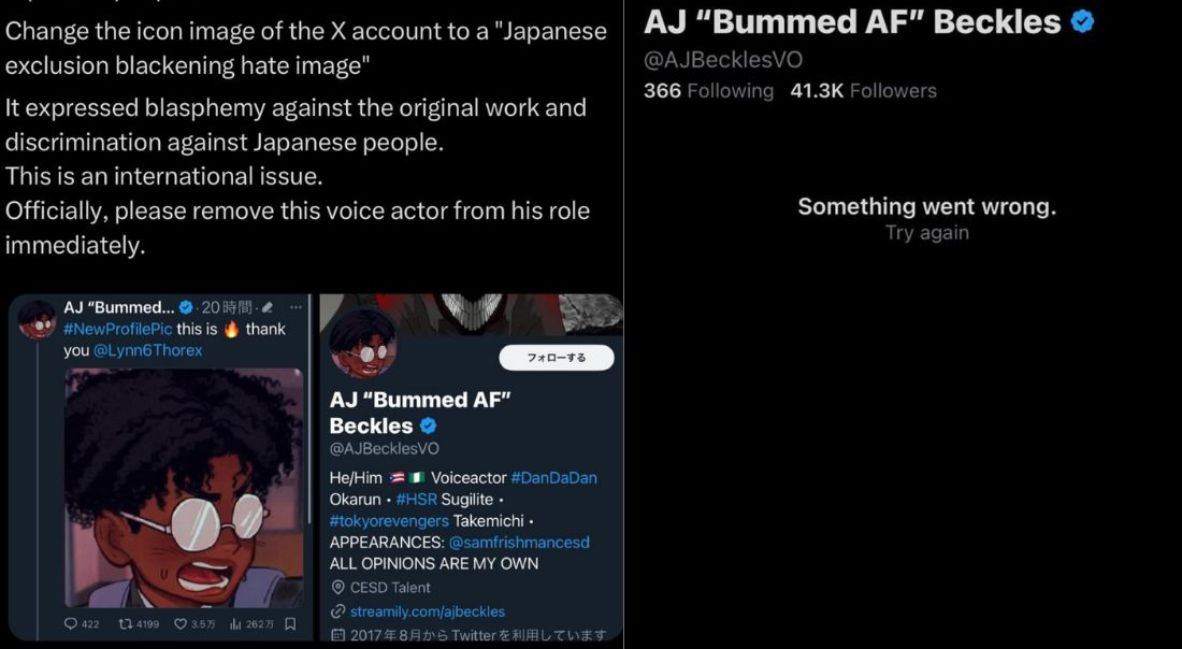

This was evident in the backlash surrounding some fan art of Dandadan and one of the show’s voice actors. In 2024, AJ Beckles, the Black voice actor of Okarun, faced massive backlash and racist online harassment after posting fan art of Beckles’ character reimagined as Black.

The fan artist intended to create art of the Dandadan character that represented the voice actor’s race, to express gratitude for Beckles’s work, and provide a reimagined presentation for many of the show’s Black fans.

The situation escalated with both the artist and AJ Beckles receiving hateful comments and being accused of “blackwashing” and being disrespectful to the source material. Keep in mind that race-bending or reimagining characters with different racial features is not new. Many fan artists engage in race-bending in their work.

Additionally, some people go so far as to lighten or completely redesign Black characters to “correct” or “fix” them. One is done with the intent to show appreciation and express artistic freedom, and the other is done out of hate and a rejection of Blackness.

A similar pattern emerged following the announcement of Vivi’s casting in Netflix’s live-action series, One Piece. The casting news of actress Charithra Chandran, portraying Vivi, was subjected to widespread hate and backlash, which included being misidentified as Black and accused of being “inaccurate” to the source material due to her skin tone.

These criticisms ignore both the text and the context of One Piece itself. In One Piece, Vivi hails from Alabasta, a desert kingdom heavily inspired by regions such as India, the Middle East, and Egypt, where a wide range of skin tones is common. Given that One Piece creator Eiichiro Oda has been very involved and intentional in the live-action casting, he has cast actors who better reflect the real-world places and people that inspire his characters.

The backlash around Chandran’s casting revealed less about faithfulness to the source material and more about how uncomfortable some fans become when characters of color are allowed to exist outside narrow expectations.

These situations are prime examples of how Black talent and representation in anime spaces are routinely heavily policed and subject to hate.

In both cases, the reaction was not rooted in canon accuracy or artistic critique, but in a refusal to accept Blackness, or rather, the proximity to it as being fitting within anime. These responses highlight another recurring issue: representation may be applauded in abstract, but when it becomes visible, embodied, or affirmed, it is often met with hostility rather than support.

The Cost of Exclusion in Fandom Spaces

This gap between progress and accountability doesn’t only exist within the industry; it extends into fandoms, too. Black anime fans, particularly Black cosplayers, are frequently subjected to harassment, gatekeeping, and racialized bullying. As a cosplayer myself, I have received my fair share of racist comments on my posts for years.

Black cosplayers are repeatedly told our cosplays are “inaccurate,” that we are “forcing race into anime,” or that they do not belong in the community at all. These attacks are not isolated or harmless, ignorant opinions; they are part of a bigger pattern of exclusion and hate.

Sadly, sometimes this racist online harassment of Black fans and cosplayers can even lead to serious mental harm and or suicide. In late 2025, a young Black cosplayer, Ash, also known as @squidkid1111, tragically passed away by suicide at 19. Ash was known for cosplaying various characters that are traditionally Asian and or white, which resulted in them receiving a lot of racist comments and attacks online. Ash’s Instagram page stated that their death was primarily influenced by online racism.

Ash is a devastating example of how, when Black fans are incessantly invalidated, attacked, and dehumanized for simply participating in fandom communities, the consequences can be dangerous. This is not just about representation; it is about safety, respect, and whether the industry that so many Black fans love is willing to protect or defend the Black people it profits from.

If the anime industry truly wants to celebrate diversity, it must also confront how its communities and fandoms treat Black fans and talent in practice and denounce that hate and harassment.

How do we fix anti-blackness in anime?

Actual progress requires more than individual improvements. It requires continuously calling out the persistent problems in the anime industry. Problems include outdated character designs, such as One Punch Man’s Superalloy Darkshine, whose background and original design are problematic because they feature elements traced back to racist caricatures.

Or reckoning with Toei Animation’s whitewashing of Usopp’s skin tone in One Piece, when even creator Eiichiro Oda has emphasized that African features inspire the character’s design.

It also means recognizing that change requires sustained involvement from Black creatives and talent themselves. Luckily, more Black talent, in addition to Megan Thee Stallion, Viola Davis, Jaden and Willow Smith, Idris Elba, and others, are actively engaging with anime studios and projects.

The involvement of these prominent Black celebrities signals a future in which more Black creatives are not only represented but also empowered behind the scenes. By having more Black and other people of color artists, voice actors, and creators involved in anime production, they are empowered to help shape it from the inside out.

The anime industry needs to make more concerted efforts to acknowledge their Black fans and talent, whom they profit from and who experience targeted hate, simply for existing and participating in fandoms.

Actual lasting progress in reducing or eliminating anti-Blackness in anime will not come from isolated wins or surface-level gestures. It will come from reinforcing that anti-blackness should not exist in the industry or fandoms.

Change will come when Black characters are allowed to be diverse, nuanced, and intentionally designed. And when Black creators and performers are given real opportunities, and where Black fans are protected rather than punished for loving the medium.

Anti-blackness in anime is not the problem of one person, company, or group to fix. It is on all of us to call it out and to hold the industries and fandom communities to a higher standard. And while the work is not done yet in the anime industry, we are getting somewhere.