Pluribus begins with a simple rupture: violence stops. Not crime alone, not war alone, but the everyday capacity to harm that underwrites how humans organize land, labor, animals, and one another. The series created by Breaking Bad‘s Vince Gilligan never treats this as a miracle or a solution. It treats it as a stress test.

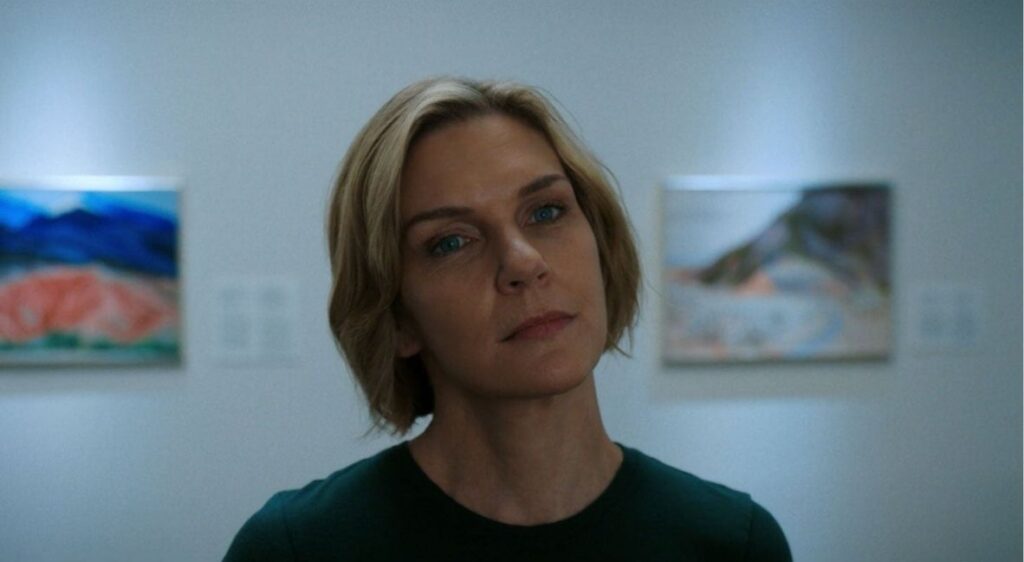

Carol, a writer already struggling with grief and isolation, becomes the lens through which the show explores that collapse; not because she understands it best, but because she keeps running into what she can’t read. Early in Pluribus Season 1, Carol (Rhea Seehorn) makes a series of deliberate choices that reveal how she moves through the world. Not simply what she values, but how narrowly she understands meaning itself.

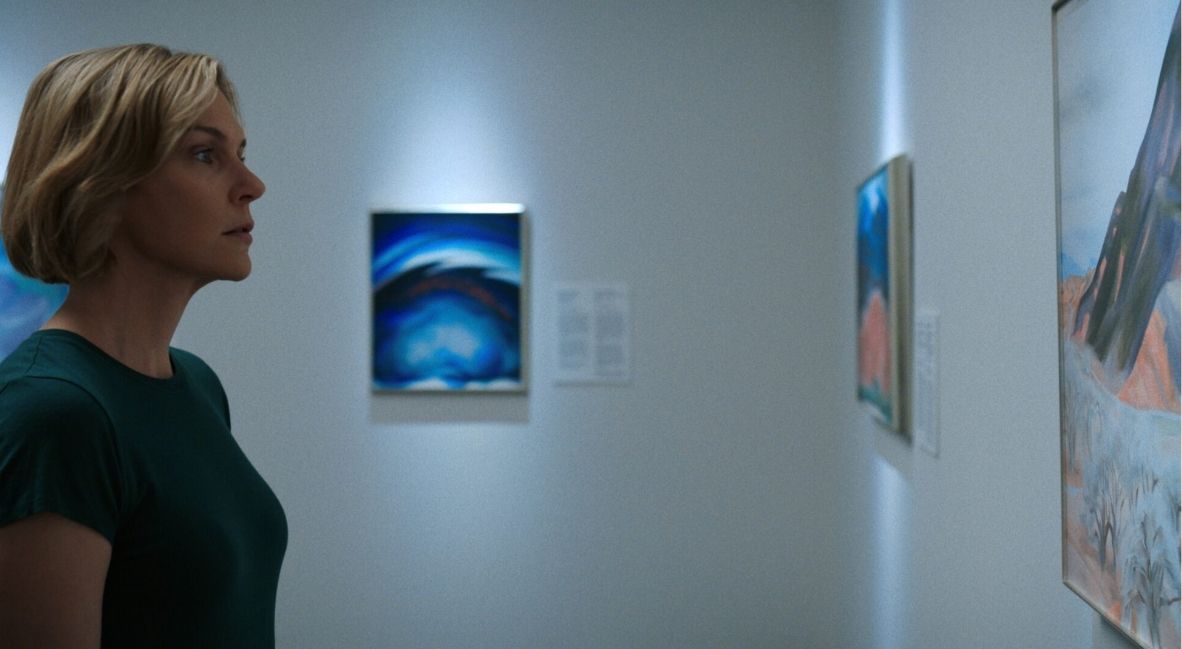

In Episode 7, “The Gap,” those limits crystallize through a quiet but pointed reference to Georgia O’Keeffe, an artist whose work exists precisely because language, ownership, and surface-level interpretation were never enough. Carol believes she understands O’Keeffe. She does not.

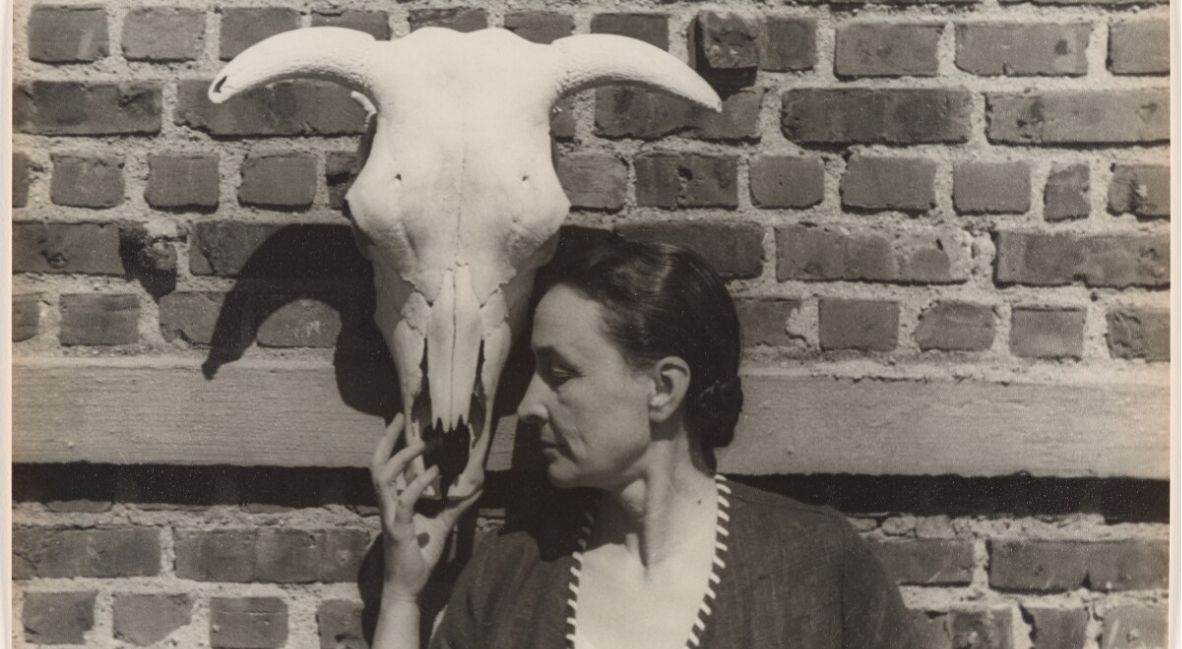

O’Keeffe’s art was never about objects. It was about attention. About staying with a place long enough to register what endures after displacement, extraction, and loss. Born in 1887, O’Keeffe came of age in an America already shaped by the near-erasure of Indigenous life and the systematic destruction of landmark species like the American bison. Her work emerges from that aftermath. Skulls, flowers, mesas, roads, and bones appear not as decoration, but as records of survival embedded in the land.

Carol gravitates toward art that doesn’t challenge her to change how she understands the world.

In multiple interviews from the 1920s and 1930s, O’Keeffe explained that she painted because words failed her. “I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way,” she reflected in 1976, late in her life. The art exists because ordinary language and ordinary ownership could not carry the weight of what she was trying to hold. Carol moves through the O’Keeffe Museum as if words have never failed her.

During Episode 7, she passes painting after painting without pause until she lingers briefly on “Mesa and Road East (1952)”. The image is defined by a road cutting through the New Mexico landscape, human movement etched into geology.

It is a painting about presence and consequence, about what it means to cross land and leave marks that do not disappear simply because the traveler moves on. “The Gap” visually echoes this image with Manousos’s journey elsewhere in the story, where terrain dictates survival rather than convenience.

She continues on to “Bella Donna (1939)”, removes the original from the wall, and takes the painting home to place a cheap reprint. The act is framed as protection, even preservation, but the choice reveals something else. Carol gravitates toward art she already recognizes, art that can be possessed, relocated, and explained without requiring her to change how she understands the world.

Carol never engages with the tension between beauty and danger in “Bella Donna.”

That matters because “Bella Donna” was itself an act of resistance. O’Keeffe painted it while in Hawaii in 1939 after being sent there by the Dole Pineapple Company with the explicit expectation that she would produce promotional pineapple imagery. Instead, she painted native plants, including deadly nightshade.

She refused the commission’s intent and redirected her attention toward what colonial agriculture was trying to replace. The softness of the white flower and its toxicity exist together. Beauty and danger share the same form. That tension is the work.

Carol never engages with it. Instead, the painting becomes an object that needs saving. Something that will look nice in her suburban living room. When the Hive returns in Episode 8, “Charm Offensive,” Bella Donna hangs in Carol’s home beside a framed black-and-white photograph that reads as urban and East Coast–coded. The pairing feels unexamined.

O’Keeffe spent years pushing back against how photography flattened her work into spectacle, particularly the way her husband Alfred Stieglitz’s photographs sexualized her body and simplified her relationship to form and scale. Carol places the painting next to a photograph without hesitation, collapsing history and resistance into decor.

O’Keeffe’s work rejects the idea that preservation means freezing things in place.

When asked why she took the painting, Carol points outward. Wolves. “Buffalo,” then “buffalos,” misnaming the animal even as she tries to correct herself. She imagines bison wandering into museums and rubbing against paintings, threatening art with their bodies. The anxiety is revealing. Because in reality, the animals are not destroying anything. They are reclaiming space.

Earlier in episode 7, Carol drives past a bison standing on a golf course in Albuquerque and does not stop. The American bison, a keystone species deliberately driven to near extinction to clear land for settlement, now stands on manicured leisure infrastructure built atop that violence.

Carol lights fireworks, shouts at wolves for making noise, and sings about being fine while moving through a world that is actively rebalancing without her consent. The bison registers as an inconvenience she has already passed.

O’Keeffe painted bovine skulls because she saw continuity in loss. In a 1936 letter, she wrote that the bones she collected in the desert “seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive.” O’Keeffe’s work rejects the idea that preservation means freezing things in place. Carol preserves art while ignoring the conditions that produced it. She saves images while walking past living history.

Even the Hive can’t stave off Carol’s skepticism.

Even when the Hive offers her a glimpse of collective rest and safety, bodies sleeping together, faces relaxed, people smiling without fear, Carol remains skeptical. She smiles briefly but does not reach out. When she returns to her theories, the conclusion she fixates on is still consumption. Humanity is reduced to threat management, not relationships.

Later, Manousos (Carlos-Manuel Vesga) challenges her directly when he asks whether it is ethical to value an ant the same as a human. The question is not a philosophical trap. It is a scale problem. From far enough away, individual distinction collapses. Systems matter more than singular intent. Carol cannot sit with that shift.

At the end of “Charm Offensive,” Carol looks out over the New Mexico landscape and remarks on its beauty before fixating on the train cutting through it. She calls the horn the loneliest sound in the world and admits she loves it, framing the moment as a private truth finally revealed. The land remains background. The confession remains centered on her.

Carol never commits to the kind of seeing that Georgia O’Keeffe did.

O’Keeffe went to New Mexico to unlearn the idea that the world existed to be explained or owned. She stayed long enough to let the land change how she saw, accepting the risk of attention in a country that did not reward women who refused simplification. When she wrote in 1939 that “nobody sees a flower really,” she was naming the time and humility required to look without trying to control what you find.

Carol never commits to that kind of seeing. She moves quickly, preserves what she recognizes, and mistakes familiarity for understanding. As an author, she believes in narrative control, but she cannot imagine the risks O’Keeffe took when language failed, and attention became the work itself.

Pluribus does not reference Georgia O’Keeffe to elevate Carol. It uses the American Modernist as a contrast. Carol treats Georgia O’Keeffe’s art as something to own and protect, revealing how little she understands the land, risk, and attention O’Keeffe lived for. The art is there. The land is there. The meaning is there. Carol simply never stays long enough to see it.