Antlers was one of the last films I was supposed to see before the pandemic started. Announced in 2018, set to release in 2020, the film is finally here and it’s a grotesquely gorgeous one at that. Directed by Scott Cooper, the film is based on the short story “The Quiet Boy” by Channel Zero creator Nick Antosca, with Antosca, Cooper & Henry Chaisson serving as the film’s writers, and is produced by iconic master of horror Guillermo del Toro. Antlers stars Keri Russell, Jesse Plemons, Jeremy T. Thomas, Graham Greene, Scot Haze, and Rory Cochrane.

Antlers takes place in isolated Oregon, where Julia (Keri Russell) is acclimating to life in her childhood home with her brother Paul (Jesse Plemons), and the trauma that comes with the house. And school isn’t much better, as she struggles to get her students engaged, she finds herself pulled into Lucas’s (Jeremy T. Thomas) life. A sullen face, quiet demeanor, and a darkness rustling under the surface showcased in his artwork, Julia notices abuse, seeing herself in the child. That said, Julia’s fears of abuse are just the start when it’s revealed that there is something darker living in the boy’s home which all leads to terrifying encounters with a legendary ancestral creature: the Wendigo.

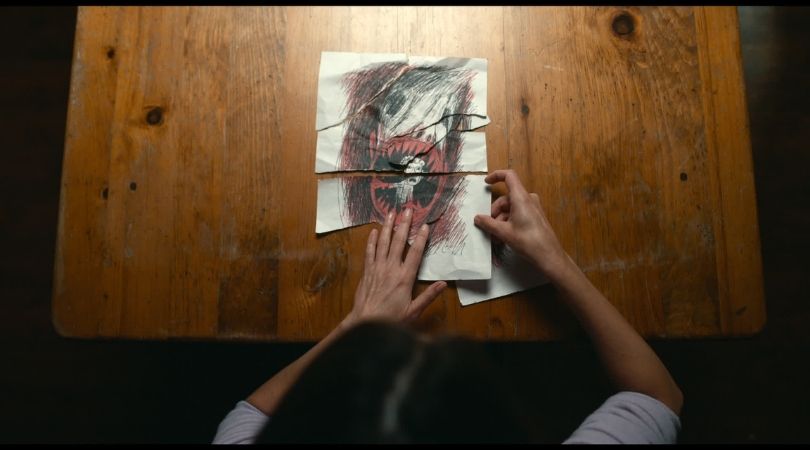

The film is a not-so-subtle exploration of the cycle of violence and trauma that is facilitated by familial abuse with the Wendigo embodying not only the corrosion of the land by mining but drugs as well. First, we see Lucas and the Weaver family with a striking opening sequence that jumps immediately into the horror with the mysterious creature make its first appearance. Thomas’s performance as Lucas is show-stopping and haunting.

For such a young actor to bring both a sense of fear, resiliency, and callousness in such distinct ways from scene to scene is breathtaking. From his physical appearance to his tone of voice, Lucas is clearly a child who has been through trauma. As the film’s intro reveals his father’s drug issues and position in selling meth, it’s clear that his role of protecting himself has existed long before the Wendigo came back home from the mines.

His struggle to protect himself and his family is echoed in Julia’s life with her brother as she struggles to face the memories of abuse and the guilt of leaving her brother behind when she left home. Over the course of the film, we see Julia morph from someone who has survived but with scars that are still healing, by the end, into a woman who has embraced her trauma as a way for her to save those around her. Putting aside her emotions to do what needs to be done in the film’s end.

Both Russell and Thomas are perfect anchors to the film, grounding Antlers in a narrative that explores survival and our inability to sometimes escape the cycle. They’re powerful on screen, especially when together. And their chemistry and vulnerability is only enhanced by the film’s beauty. Somehow, even in large sweeping landscapes, a lot of Antlers feels claustrophobic and cold. As the Wendigo becomes more prominent there is a fire to the scenes that becomes overwhelming and the film’s effects team was working overtime to bring a creature worthy of Guillermo del Toro’s producer credit to life.

From mangled bodies to husks, there is a grotesque beauty to Antlers that showcases is an understanding of body horror that takes the Wendigo and the harm it causes to the next level. Additionally, the use of sound in moments of excruciating body horror will make you squirm. For effects, acting, and design Antlers succeeds.

That said, the film has one glaring issue that horror has fallen victim to all too often: using Native culture as window dressing for a white story. Despite having consultancy from Smoke Signals director Chris Eyre, the film treats Native culture similarly to the horror films that came before it. In fact, the Wendigo terrorizing the white family, when coupled with the film’s opening “warning” recited in an Indigenous language, feels too much like “white people disturb Native land and are punished.” Add in the fact the film’s only Native character with over three lines plays a version of the Magical Native American and is only there to explain the Wendigo to the protagonists, and it’s hard to not be taken aback by it all.

Sure, getting the Wendigo “right” is one element, but by setting threads of Native culture that aren’t explored and instead used to decorate the narrative, Antlers falls short. If you’re going to lean in, lean all the way in and center Natives in a story. To call this folkloric horror is to ignore that the stories being taken from Natives isn’t folklore or myths, but seen as a reality.

Folkloric horror, when done right, understands the importance of the stories not just in how it can scare audiences, but the power the stories have in the cultures they belong to. Good folkloric horror looks at folktales and understands what they mean to communities and more importantly when they’re more than just a myth, but a way of life. Antlers isn’t good folkloric horror because it misses those points.

Overall, Antlers is a film with stunning performances, uncomfortable themes, body horror, and beautiful effects work. It’s a mean film that ends with a punch. But alas, it’s still a horror film that wants Native culture without actually incorporating Indigenous people as more than tropes.

Antlers is playing in theaters nationwide October 29, 2021.

Antlers

-

Rating - 7/107/10

TL;DR

Overall, Antlers is a film with stunning performances, uncomfortable themes, body horror, and beautiful effects work. It’s a mean film that ends with a punch. But alas, it’s still a horror film that wants Native culture without actually incorporating Indigenous people as more than tropes.