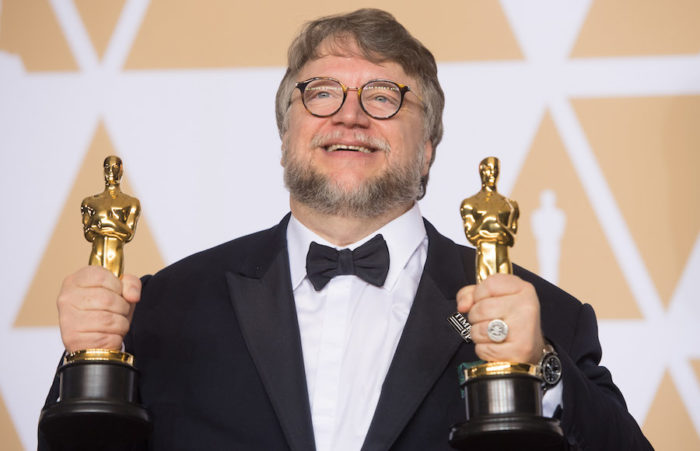

Guillermo del Toro is the Best Director of the 90th Oscars. This win is important for a number of reasons and can be attributed more largely to creators of color and other underrepresented/marginalized groups doing work in the little-recognized realm of genre film. This film distinction refers to genres of film like fantasy, science fiction, horror, and comedy. I didn’t think it would be fair to Jordan Peele or his Oscar-winning horror movie, Get Out, to be sandwiched into an article where the main focus is del Toro and his work. But let it be noted here, loud and clear, Peele directed a horror movie which broke the box office and won an Oscar, as well as numerous other awards, a feat even white genre director people rarely accomplish.

Although the struggles of a black man in film and a Mexican immigrant are not equal, they are similar; both men have fought systems to earn these achievements and did it on their own terms, in genre film and through their personal experiences of marginalization. The importance of Get Out is something I can speak to only a small degree, as a Chicana – used to refer to Mexican-Americans and our fight for civil rights and more specifically used to denote Mexican-Americans who are native to the US – I identified within how I navigate white spaces and the fear I feel in certain parts Texas, I’ve been used for my labor, looks, or other stereotypes. That being said, I do not experience this film as a black viewer would, since I do not live a life with Chris’ (the main character) experiences, that of being black in the US. If you would like analysis on this check out these articles written by black writers here and here. You can also hear director Jordan Peele’s interview on All Things Considered talking about tackling race in horror, here.

The core of my article is this; When you represent an underrepresented group you bear a burden to perform to perfection. There is an expectation set on you by those both inside and outside of your community. This “burden or representation,” a term used by the Cultural/Media Studies scholar Stuart Hall, is what drives outside communities to ask us to tell our pain and trauma and history, while also causing a sense of guilt when we deviate from doing so in our creations, or haven’t met the unattainable standard of perfection for all.

For Chicanos, this means we are burdened to show our lives in films as commentary on gang life, immigration and the death that can happen, the exploitation of undocumented labor, our employment as sanitation workers -janitors and maids – and the fight for equal rights like Cesar Chavez (Diego Luna, 2014). These films are often serious dramas that draw on historical narratives or personal tales of struggle and triumph. Beyond that we must push back against negative stereotypes with the representation we offer through our stories, which often leads creators struggling or taking movies that reinforce harmful stereotypes: the prisoner, the cartel, immigrants putting Americans out of work.

The burdens of representation often pushes them to only create dramas and/or biopics or their history of oppression or to take on stories grounded in negative and harmful stereotypes associated with their culture. This doesn’t diminish those works, in fact movies like American Me (Edward James Olmos, 1992,) Stand and Deliver (Ramón Menéndez, 1988), Under the Same Moon (Patricia Riggen, 2008), Selena (1997), and Cesar Chavez (2014) are all important to the Chicano experience and each give some insight into being Latinx in the US from the Mexican-American perspective. However, these necessities to Chicano cinema all focus on historical figures or the pain and discrimination we have gone through. These stories are important and they need to be told so that generations after us and those outside our community can understand our stories from our hearts and talents, not through a creator outside of communities. But too often, this is the only expression that marginalized creators tell, leaving them out of genres such as horror, science fiction, and fantasy.

However, drama and biographies are not the only way to explore discrimination, fear, anxiety, and trauma. Although Guillermo del Toro is not Chicano, he is a Mexican immigrant, his stories work to uplift our communities in the United States which have been demonized and marginalized by politicians and media outlets. By showcasing our talent they present a counternarrative to the presentation of Mexicans as “criminals and rapists”.

Genre film is often looked down on for not being serious, or real enough because of its use of comedy, monsters, scares, or fairy tales, genre film is regulated to the sidelines of award season, nominated but not voted unless it is in technical category – with the notable exceptions of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (Peter Jackson, 2003) and Silence of the Lambs (Jonathon Demme, 1991) bringing home awards in all major categories, and I’m sure one or two I’ve missed. Genre film is often seen as low-brow movies that do not showcase important elements of human life or struggle. That being said, horror, as it exists as a genre, is only successful when the director and writer show the audience their deepest personal and/or societal fears. These are directly influenced by the culture the horror story arise from, making them the perfect platform for examining issues of marginalization. One fear that is constantly shown for women in horror, for example, pregnancy and “devil children” is often used in horror to showcase the fear of impending motherhood as well as the fear of not knowing your own child.

The importance of horror and its ability to terrify the viewer comes specifically from the unease of witnessing images or words in front of you and the exploitation of your connection with the material which is built through empathy with the character in front of you. Similarly, fairy tales were originally used to elicit fear, to teach lessons, and to ultimately tell a tale relevant and informing the society it emerges from. For this reason, genre film like horror and fantasy do the work of historical dramas while using symbolism, metaphor, and more stylized techniques to talk about societal fears and problems, making these genres the perfect mediums for exploring lives and issues marginalized groups deal with.

For Guillermo del Toro, monsters have been the way that expressed himself. Growing up in Mexico he taught himself English by reading old Universal Monster movie magazines and found solace in monsters, he saw himself in them. For him, like many outcasts, monsters of that period are often misunderstood and empathetic creatures not seen by the world first but ostracized or hunted. It was this significance he found in monsters that secured what del Toro would do in his own career. Aware of the power of monsters, he set on a career that told fairy tales and used elements of horror to build worlds that addressed the real world but were visually fantastic and creatively new.

One of the things that is easy to say is that Guillermo del Toro as a white-latinx man and therefore is privileged. While this is true, his white-passing privilege allows him to pass through spaces I or afro-latinx members of our community can not, or in different ways. That being said, he is marginalized by his accent, immigration status, and his name, all of which mark him as the Other in the United States and have crafted a negative immigrant experience, which he has talked about. His status an outsider led him to only be given scripts for “drug cartels and mariachis,” in his own words. From his Mexican roots, his drive to create monsters and tell fairy tales made him unbillable by the Mexican Film Institute, which – like all film institutes in Latin America – prioritized dramas and history as the only way to make an impact and represent Mexico to an international audience. To make his films and tell his stories, del Toro had to push against those around him, from his homeland and his new home which he fled to after his father’s kidnapping after his first US contract.

However, when watching his films, they’re Mexican, and uniquely so:

“When people say “what’s Mexican about your movies?” I say, “me.” It’s just a special brand of madness that makes us make alebrijes that’s more important than having nationalistic values to me. The one thing we need to reclaim as storytellers is to have no shame. When I went to America they kept giving me mariachi, drug dealer [stories]… you wouldn’t give that to Cronenberg.”

Instead of taking the road already traveled, Guillermo del Toro made his own path, telling stories of abandonment, civil war, identity, and acceptance. His protagonists are almost always women and girls rewriting the common fairy tale/fantasy tropes around them, as well as boys and men being shown the lighter sides of fantasy, not just as fighters. He’s said, “It’s important for little girls to know not every story has to be a love story and for boys to know that soldiers aren’t the only ones to triumph in war.”

The most memorable example of showcasing pain while also weaving a fairy tale and showcasing dynamic and beautifully terrifying creatures and monsters comes in Pan’s Labryinth (2008). In Pan, we follow a little girl, Ofelia, in the midst of the Spanish Civil War who ends up on a quest to be turned into a princess. When she is ultimately killed, del Toro shows that in this world of pain and war imagination and death are the only two escapes. In the epilogue, he explains that Ofelia’s presence on earth can still be felt by “only to those who know where to look,” imploring us to look for the fairy tales, the stories, the imagination to save ourselves.

Although Pan brought home awards from the 79th Oscars, they were in technical categories, Art Direction, Cinematography, and Make-Up. These awards are the ones reserved for films not deemed good enough to fit the bill of dynamic storytelling. To put in perspective, Suicide Squad (David Ayer, 2016) has one Oscar, and Bladerunner: 2049 (Roger Deakins, 2017) has two, all three statues won from technical categories. Now, in 2018, Guillermo del Toro earned another shot at the golden man, and this time with a movie he expresses is the film that has been in his mind for the past 25 years. Not only was it a shot, but with 13 nominations, he led the pack.

In The Shape of Water (2017), del Toro tells the story of Elisa (played by Sally Hawkins), a mute woman who works as a cleaning lady in a hidden, high-security government laboratory in 60s Baltimore. Her life changes forever when she discovers the lab’s classified secret — a mysterious, scaled creature from South America that lives in a water tank. As Elisa develops a unique bond with The Asset, she soon learns that its fate and very survival lies in the hands of a hostile government agent and a marine biologist.

She is surrounded by friends who are Others in the world, like her and The Asset. Her neighbor, a gay man named Giles played by Richard Jenkins who deals with homophobia hurting his life, and her best friend and co-worker, a black woman who deals with racism and sexism at the lab, Zelda, played by Octavia Spencer. As she falls in love with The Asset, they see her changing, Elisa is happier, accepted, and whole. When she learns that he is about to be killed and sees him tortured, she hatches a plan to save him. Initially hesitant, she shows her friends that although The Asset may not be human, if they do nothing, neither are they.

Although this is a monster movie, it is also a love story and a fairy tale that was written to showcase that those who act in ignorance and bigotry are the real monsters. The love story, as del Toro has said, is not like the typical beauty and the beast narrative in that it isn’t about changing. In most fairy tales, the beast who is ostracized and depicted as other and wrong is saved by beauty by ultimately changing to suit her and society’s needs.

The humanizing of monsters has always been Guillermo del Toro ’s goal, in fact, he sees horror and monsters as his religion, and monsters as his saviors in troubled times. I’ve tackled how empathy for the creature in del Toro films has shaped his particular style of horror in the past. For The Shape of Water, this story is about true love, in accepting and appreciating the differences as necessary and beautiful and also fighting against a world set up to separate you – a reality felt by many families in the US with different citizenship statuses right now. It is also a story about realizing that when the option to act arrives, it is silence that leaves us complicit in acts that are hurting others, therefore furthering their suffering. In the story, the characters are moved to action and in the end it is the racist misogynist agent who has been harassing Elisa and torturing The Asset who is killed and disfigured, turned into the monster visually to match the monster inside.

Guillermo del Toro’s Oscar wins for Best Director and Best Picture show that these stories of acceptance, love, and suffering are ones that can be told through the lens of fantasy and horror. Too often creators from marginalized communities are made to feel less than by those outside their communities and those inside of it for choosing to make movies that do not speak to specific causes outright. Especially when that looming burden of showcasing their communities weighs their decisions. Del Toro’s win, as well as Peele’s win for Best Original Screenplay for Get Out (which used horror to talk about the fetishization of Black bodies, pervasive liberal racism, as well as other important issues in our country today and force the audience to confront it), prove that fantasy and horror is not only able to be considered high art but are also vital genres to tell the stories of horrific times and real experiences.

Having started producing the movie before the election of Trump, reporters like the LA Times asked Guillermo del Toro if he had these central issues of racism and discrimination in mind:

“I did. And the reason why is that I’m Mexican. I’ve been going through immigration all my life, and I’ve been stopped for traffic violations by cops and they get much more curious about me than the regular guy. The moment they hear my accent, things get a little deeper. I know it sounds kind of glib, but honestly, what we are living I saw brewing through the Obama era and the Clinton era. It was there. The fact that we got diagnosed with a tumor doesn’t mean the cancer started now. Hopefully one of the things the movie shows is that from 1962 to now, we’ve taken baby steps — and a lot of them not everyone takes. The thing that is inherent in social control is fear. The way they control a population is by pointing at somebody else — whether they’re gay, Mexican, Jewish, Black — and saying, “They are different than you. They’re the reason you’re in the shape you’re in. You’re not responsible.” And when they exonerate you through vilifying and demonizing someone else, they control you.I think the movie says that there are so many more reasons to love than to hate. I know you sound a lot smarter when you’re skeptical and a cynic, but I don’t care.”

When you look at the greats of fantasy and horror you hardly find creators from marginalized communities. These genres have privileged white voices, largely because they are seen as being escapes and seen as only leisure. They have the ability to write fairy tales because there are other people doing other work in the industry, if they don’t make a film about a world event, there will be someone else who will. For people of color and marginalized groups, often have to tell ALL the stories of their community and bear the burden of the narrator, actor, teacher, creator, and savior all at once. People don’t expect to see stories of racism and otherness in horror, they don’t expect to see tales of acceptance and immigration in a fairy tale. But for many, imagination is how we escape our trauma, it is the place we go to see ourselves and explore ourselves. With stories that use fantasy and horror to talk about fundamental truths, whether it is acceptance through love like The Shape of Water or exposing the insidiousness of liberal racism and fetishization like Get Out, I hope and expect to see more marginalized groups hitting it big.

I want to see more Guillermo del Toros and Jordan Peele’s rising and joining genre films, as well as an elevated place for those in the genre right now who are often overlooked by critics, like Asian-American Karyn Kusama. Genre film was recognized by the Oscars this year, but it has also been recognized online, in the hearts of people who see their stories explored on screen, and by directors who are doing this on their own terms. In addition to del Toro saying that genre can be used to tell real-world stories in his Oscar acceptance speech, Peele, when accepting his award, explained that he had stopped writing Get Out 20 times because he thought that it wouldn’t work, but as he kept pushing he knew that if someone saw it, they would really see the story.

With A Wrinkle in Time (Ava DuVernay, 2018) releasing this weekend nationwide and Alita: Battle Angel (Robert Rodriguez, 2018) debuting at the end of December, and others I haven’t mentioned, diversity in genre films this year is more than I have seen in a single year. Specifically for black and Latinx representation, the latter I have listed here. I’m hoping that this year with these successes more marginalized storytellers will explore where their hearts take them, and if that is fairy tales, I hope they make everyone feel their magic.

The only way to end this piece is with the final words of Guillermo del Toro ‘s acceptance speech:

“I wanna tell you, everyone who is dreaming of a parable, of using genre fantasy to talk about things that are real in the world today, you can do it. This is a door, kick it open, and come in.”