The Smashing Machine, distributed by A24 and written and directed by Benny Safdie, has two goals. It is a vehicle for Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson to flex different acting muscles than usual by playing a dramatic role. It is also an attempt to bring notoriety to Mark Kerr, a pioneer in mixed martial arts (MMA) in the late ’90s and 2000s. Kerr is a complicated figure. He’s exceedingly kind towards others, but brutally hard on himself and is constantly fighting with his girlfriend, Dawn (Emily Blunt).

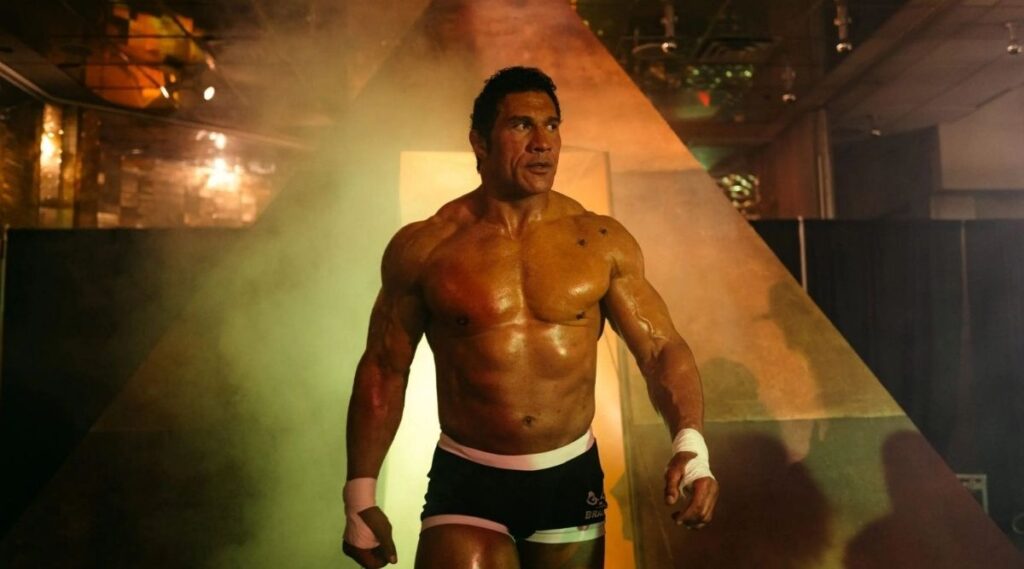

The Rock physically transforms to play Mark Kerr. He can’t hide his 6-foot-4 stature, but his full head of curly hair is anomalous, and the distribution of his muscle mass is notably different from the typical action movie type of buff he dons. It’s almost enough to let the former pro-wrestler completely hide himself in this close-to-home role as a pro-wrestler who transforms himself into an MMA fighter.

The Smashig Machine comes close, but can’t fully escape The Rock’s orbit.

However, Johnson cannot hide his next-most notable characteristic, no matter how hard he tries—that he is naturally as a grade-A cornball. This mostly works to The Smashing Machine’s advantage. Kerr, in The Smashing Machine, like The Rock in many of his on-screen roles and real-life appearances, is an overly genuine and somewhat gentile figure. Hence, The Rock’s perfect casting.

The inescapable tone of voice that Johnson takes from the beginning through the end settles you into the notion that this is a truly thoughtful man who is working hard to become the person he sees himself as. The trouble is in fully believing him.

Because of that overly genuine and somewhat gentle tone of voice, you have to work extra hard to separate pre-conceptions about The Rock from the character he’s portraying, despite the clear and intentional similarities. You also have to work just as hard to tell how much Kerr means the things he says, even though he always means every word.

The Smashing Machine is shot like a documentary, distancing the characters too far.

The cinematography and editing further blur the lines between where Johnson ends and where Kerr begins. During action scenes, the movie is shot with typical close-ups. And, while in Mark and Dawn’s home, it’s shot with a tracking camera that follows the two around the house as they fight, making the house itself somewhat of a character.

However, too often, especially during critical emotional scenes, The Smashing Machine is shot from a distance, emotionally and physically. Much of the movie is built around interviews between journalists interviewing Kerr or other fighters talking about him. The big fights are all covered in voiceover from announcers, as if you were watching them on pay-per-view yourself—albeit, with more film-like camera angles and audio from much closer to the ring. The film is even presented in an old-school, narrow and tall aspect ratio, opening with a VHS-quality fight sequence from Mark’s early professional days.

Then, when things become emotional, especially between Kerr and his closest friend, trainer, and sometimes opponent, Mark Coleman (Ryan Bader), the camera goes over people’s shoulders, punches in and out awkwardly mid-sentence, and keeps the subjects at a distance. All of these components set The Smashing Machine up to feel like you’re watching a documentary-style movie. The characters become subjects being studied rather than active participants in their own story.

Despite neat intentions, The Smashing Machine gets stuck in typical sport drama slosh.

The intention is perhaps to demonstrate how Kerr keeps his friend at a distance. How, by letting Dawn in too close, it often set Kerr down darker paths than if he kept Coleman in that closeness instead. It may also be a metaphor for what it’s like to become addicted to drugs, as Kerr struggles with in The Smashing Machine. But the result is a biopic that feels too disconnected from the most interesting parts of its story. In the attempt to service the most typical components of a sports drama, the movie swings and misses altogether.

Countless sports dramas and biopics depict an athlete, especially men, at the top of their game, toppled by drugs, ego, and women. The Smashing Machine is exactly that in a nutshell. Its plot beats are so typical and expected as to induce eye rolls at regular intervals.

The movie doesn’t punch these aspects up, either. Kerr’s drug abuse is approached with as much a cut-and-dry attitude as his whole character is built upon. The abuse is depicted once, its results are quietly shown a few times, and when it comes crashing down, that’s it: it’s dealt with in a flash and never returns to the fore

Emily Blunt’s Dawn is short-shrifted as Mark Kerr’s out-of-touch girlfriend.

The Smashing Machine doesn’t need to put Mark Kerr through the ringer of drug abuse and relapse to make the story compelling, but it needs to make either his rejection of the status quo or the lesson he learns from doing so more fulfilling. The worst of Kerr’s status quo is his constant return to his unhealthy relationship with Dawn.

The movie is significantly burdened by repeated arguments between the two. Dawn is offered no growth of her own in the movie, so she quickly becomes a cloying component of the film who drags down the energy every time she shows up to rehash the same boring arguments again and again. Tonally mismatched music plays too loudly underneath most of these arguments. It’s effective the first time, but it gets old fast.

Dawn isn’t written to be especially sympathetic either. Kerr doesn’t treat Dawn especially well, but much of their constant fighting stems from her insecurities. Kerr does try to assuage them time and again with as much patience as he can muster. It’s just that disingenuous tone of voice of his that makes it as hard for the audience to believe him as it is for her.

More Mark Coleman would have made all the difference for The Smashing Machine.

You can’t root for Dawn to win because she’s depicted as being so in the wrong. You can’t root for Mark either, because he’s so unkind to her so often. But you can’t root for them to figure it out either, because they are so clearly incomparable. There’s no winning in this overly drawn-out side of the plot.

The part of The Smashing Machine that deserved more build-up and screen time is Kerr and Coleman’s relationship. This is the emotional core of the movie. It’s their friendship and pseudo-rivalry that carry the most narrative tension and drive most of Kerr’s growth as a character.

However, because Coleman is left at such a distance, he becomes a tertiary character rather than standing equal to Dawn in the movie’s development. One brief scene at Coleman’s home with his family and a few interviews with the media help raise Coleman’s character up, but it also leaves you wanting much, much more of him than the movie provides.

The Smashing Machine takes admirable swings, but misses too many punches.

On paper, The Smashing Machine should be a stand-out movie. It has plenty going for it in The Rock’s performance and the general approach to telling this untold story of an MMA pioneer. The parallels between Dwayne Johnson and Mark Kerr are captivating, and the way that The Rock executes the performance is quite solid.

Unfortunately, because Johnson cannot entirely escape his real-life persona, the character becomes somewhat muddy. And because the screenplay focuses on the wrong secondary character, the movie quickly becomes underwhelming biopic slosh instead of the shining example of positive masculinity and struggle that it nearly is. The Smashing Machine may throw a lot of big punches, but too few of them actually land.

The Smashing Machine is in theaters everywhere.

The Smashing Machine

-

Rating - 5.5/105.5/10

TL;DR

The Smashing Machine should be a stand-out movie, but quickly becomes underwhelming biopic slosh instead of the shining example of positive masculinity and struggle that it nearly is.