Directed by Kenji Iwaisawa, 100 Meters seeks the ultimate thrill of the greatest mental endurance test this side of writing. Based on the manga written and illustrated by Uoto (Orb: On the Movements of Earth), the film places its narrative on the shoulders of characters embarking on a journey of growth through repetition. Their finish line never changes, nor do their objectives, but the means of achieving them—how they face their triumphs and overcome losses—gradually shift over time. The track remains the same, but through the ingenuity of characters, Iwaisawa and Uoto, the lens widens and highlights the specificities of life.

There’s a deceptive simplicity to the story at the heart of 100 Meters and the two characters anchoring it. Two characters who, conversely, don’t interact quite as much as one might assume based on their seeming destiny for rivalry. Instead, the film reminds us that sometimes the most integral relationships are fleeting. In the case of Togashi (Tori Matsuzaka) and Komiya (Shota Sometani), it takes place on one of the fastest battle grounds in athletics.

We first meet Togashi in sixth grade (here voiced by Atsumi Tanezaki), already known for his speed and natural gift for running. He consistently wins the 100-meter race, seemingly without effort, back straight and feet slapping in quick precision against the ground. He loves running, enjoying the boyish thrill of being good at something.

One integral interaction sets the stage.

His love and skill meet their first path divergence with the arrival of transfer student Komiya (Aoi Yūki). Togashi first meets Komiya as he breathlessly and clumsily runs past him before falling flat on his face, winded. Later, after learning his name, Togashi sees him once again sprinting around his home, ungainly and labored. Togashi runs to stop him, inciting their first real and most significant interaction.

“Do you like running?” Togashi asks Komiya. To which Komiya replies, “No, it’s tough.” And therein lies the difference, setting them on their path as they challenge one another throughout their athletic careers. Togashi runs because it’s easy. Komiya runs because it’s so difficult for him that it helps blur the lines of an even more brutal reality. Both are seeking an escape, but while one is chasing it, the other is running away.

It’s this interaction that speaks both to the strengths of 100 Meters and the enduring metaphorical depth of the act of running. It’s been explored in other media before. Run with the Wind sought the meaning of the sport and found it through camaraderie, shared experiences, and growth through repetition—running doesn’t get easier, but you learn to endure it better. Author Haruki Murakami is self-reflective in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, exploring the duality of the solo sport and solitary life as a writer.

100 Meters sees running as a mirror for life.

Where 100 Meters finds new sparks is in that short distance. Despite telling the story over the course of a decade plus, the narrative maintains a relatively rinse-and-repeat style format. A narrative cycle that helps emphasize the cyclical nature of life. We check in with Togashi and Komiya at different points in their lives as they begin to approach running from new perspectives, face off against new opponents, and seek out their ultimate desire to run the 100 meters faster than anyone because, in the youthful words of Togashi, doing so can “solve almost anything.”

100 Meters does a fine job in selling that sentiment, offering a sense of suspended reality as the characters run. Despite the short distance, the film finds new ways to convey the passage of time and the way the two pivotal characters shoulder their hardships both on and off the track.

Despite the hinted-at struggles Komiya faces, Togashi is the more interesting of the two, aided by some truly wonderful animation that lets him remain subdued but expressive. The linework around his eyes and easy grins is particularly impressive, conveying his good-natured disposition without making him an overt do-gooder.

The only time the film lags in energy is when we switch from Togashi’s high school days to Komiya’s. The latter is interesting, but there’s a kinetic, thrumming energy to the former as Togashi, for the first time, reclaims his love for running that’s hard to duplicate.

Kenji Iwaisawa brings this tactile world to life through rotoscoping.

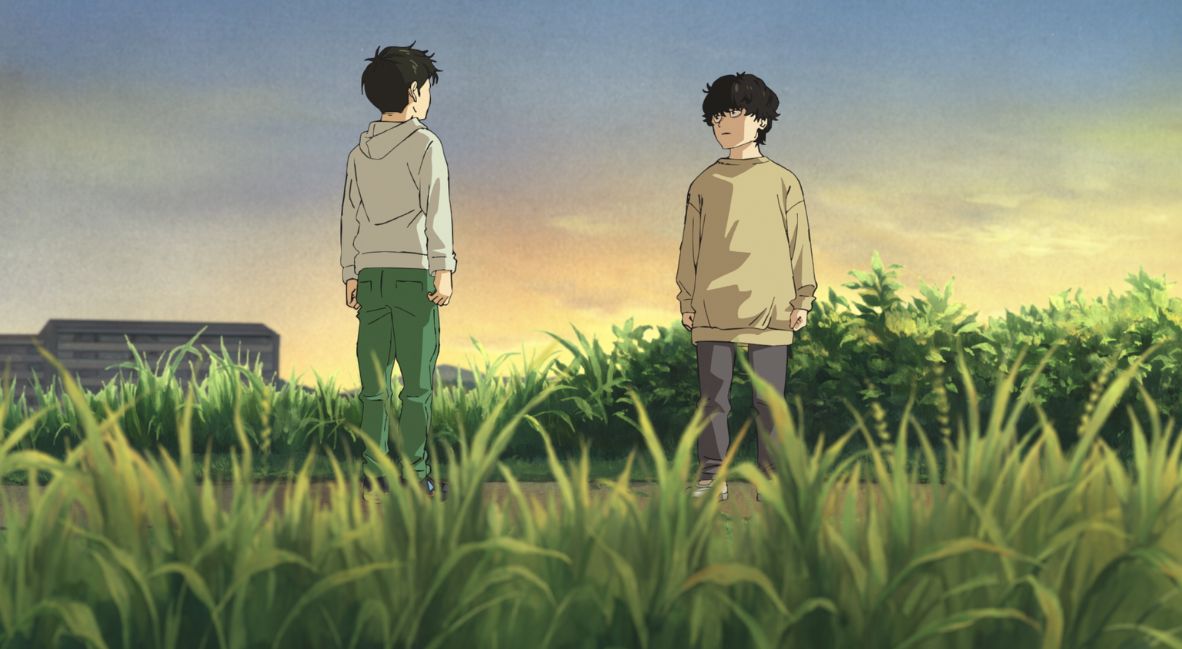

While the story itself is undoubtedly engaging and unassuming in both its tender heart and consistent comedy, the animation and behind-the-scenes talent amplify the effect. The character designs by Keisuke Kojima beautifully bring Uoto’s work to life, making the characters feel lived in and distinct as we observe the subtle signs of age over time.

The expressiveness of the characters is heightened by rotoscoping, as the running scenes give the characters as much personality as the writing does. Something as simple as one athlete holding his back at the end of the race is as effective as a young Komiya barreling through the suburban streets, head bowed rather than looking up and ahead as runners are taught.

The use of rotoscoping allows Iwaisawa to offer greater weight to running scenes. Each character has their own style of running, their own distinctive qualities, and physicality. There’s real gravity to their movement as we follow their quick steps, the musculature in how they hold themselves, from shaking out their ankles pre-race to the heaving breaths post. Iwaisawa’s direction plays with form and angles, which help emphasize when characters are at their lowest. As the characters themselves warp, the line work distorts, and hopelessness creeps in.

Beyond the characters, the animation stuns, from the softly lit days of youth to a rain-soaked competition that spells the end of one’s running career. The film refuses to lose itself in one trend or gimmick, ensuring that the landscapes are as detailed and lush as the moments on the track.

A contemplative exploration of self through endurance and repetition.

Composer Hiroaki Tsutsumi is gorgeous and electric, light on its feet with twinges of melancholy that echo the emotions of the characters. But for all of its bursts of sound, it, like the emotion and humor—the characters themselves even—is also unassuming. There’s a lot of Ping Pong the Animation in both the music and construction of this cinematic world, a soft-spoken evolution of athletic rivalries and personal goals. The idea of how one person and their easy belief can set you off on a new path of self-reckoning and triumph is inspiring.

The contemplation, despite the kineticism of the animation and the sprints that dominate the story, is what makes 100 Meters such a masterwork. It’s not just a beautifully animated film (though that alone should be championed.) But it’s a wonderfully meticulous character study that refuses overt emotional pulls or big, declarative moments. It echoes the spirit of the sport it follows – one where the most minute of details can change the course of a ten-second race.

100 Meters, in its quiet heartbreaks and subtle humor, is tremendous. A breathless and breathtaking example of the limitless possibilities for animation. A meditative look at how running represents the trials of life and our ongoing efforts to find meaning in what we love and excel at. We tackle what’s tough and hone the skills that come easily for us, all for the sake of progressing forward, regardless of how many times we have to run the same stretch to achieve the momentum.

100 Meters is available to stream now on Netflix.

100 Meters

-

Rating - 9/109/10

TL;DR

100 Meters, in its quiet heartbreaks and subtle humor, is tremendous. A breathless and breathtaking example of the limitless possibilities for animation.