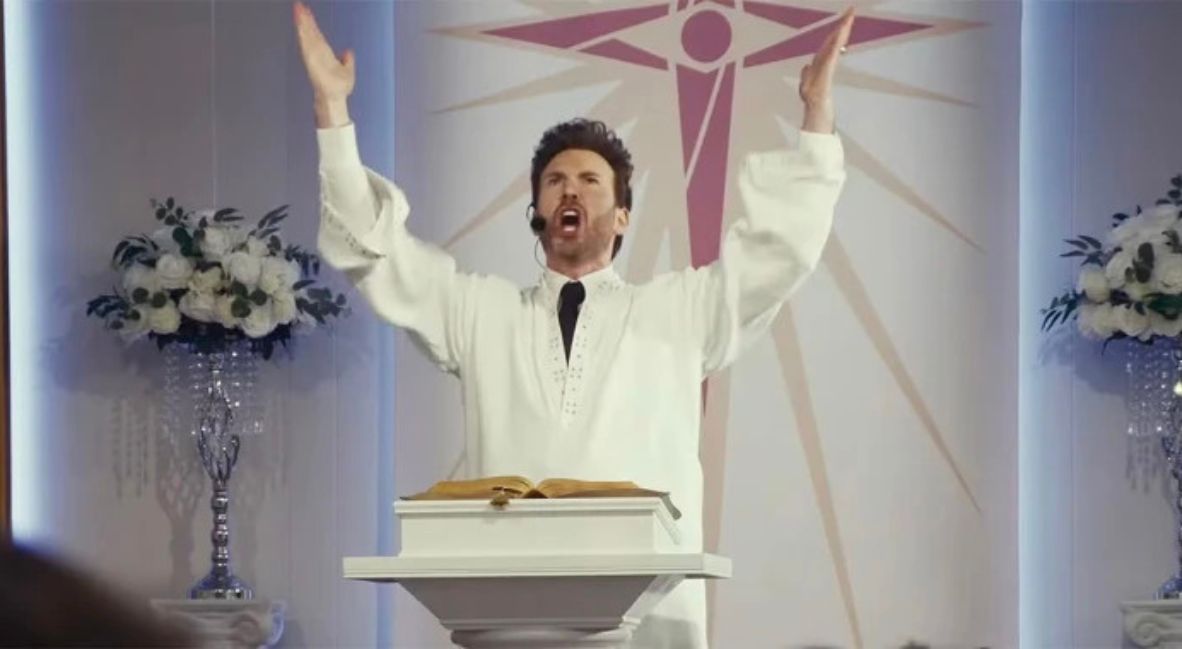

What do people fantasize more about than power, violence, and intimacy? Ethan Coen and Thricia Cook’s Honey Don’t is a genius work of subversive comedy that plays on decades of film tropes Coen himself helped establish. Margaret Qualley stars as private investigator Honey O’Donahue. A woman who just called her yesterday for help turns up dead, and the local Reverend Drew Devlin (Chris Evans) and his church are very obviously involved, somehow.

With the help of her assistant, Spider (Gabby Beans), police officer MG Falcone (Aubrey Plaza), and, sure, homicide detective Marty Metakawitch (Charlie Day) too, Honey tries to unravel what happened to the woman and an increasing string of other dead people—all this while dealing with family drama, having unbelievable bedtime soirees with MG, and wearing some of the best glute-defining outfits known to screen.

Since 1984, Ethan Coen has been part of film history with some of the most renowned neo-noir films of their respective times. From Blood Simple (1984) to Fargo (1996) to True Grit (2010) and so many more, Coen Brothers movies have always been about taking the themes they established in prior works and subverting them repeatedly but subtly.

The plot of Honey Don’t is primarily a device for introducing characters.

Conclusions aren’t always the point of their plots; characters come and go without needing to return later to have meant something at the time. Moreover, every phenomenally acted character is designed so sincerely and lovingly that it’s easy to mistake them for caricatures or strawmen. Honey Don’t is yet another excellent example of this tradition.

The plot of Honey Don’t is more of a device for delivering characters than it is anything else. The steps along the way are interesting, but they don’t always amount to much. Sometimes, Honey is just driving around looking at the small, dilapidated town she lives in for minutes on end, and nothing she looks at means anything except that it exists in that place and time. People die unexpectedly, ending entire plotlines without conclusions.

Whole characters are introduced throughout the film, only to have a significant impact in the moment they appear and then disappear entirely. Characters that seem like they would matter a great deal in a film, typically, especially a neo-noir, where supposedly some kind of crime is meant to be solved.

Every character in Honey Don’t exists in complete excess.

But those characters do matter—a lot, even. They just matter on a human level, impacting other people for brief moments that will extend long beyond the film’s purview, even if they make only a marginal difference to the story being told.

Every character exists in complete excess, but only to be luxuriated in, not to be exaggerated. Reverend Drew is a monumental, manipulative prick who takes horrible advantage of the women in his flock. It’s the better version of this similar character Chris Evans has played in his post-Captain America days. You loathe him, of course, but you also crave more scenes with his loathesomeness because of how over the top it gets with each visit.

Charlie Day’s Marty is a completely sexist and equally oblivious man who would typically be so contemptible, but because the movie loves this character, and because he’s played by somebody so beloved, he’s one of the funniest parts of the film. Most of his lines are him trying to ask Honey out, dozens of times over, despite her repeatedly explaining that she likes women. But his catchphrase is essentially “You always say that!” And it never stops being funny because you’re meant to love his antics, not scoff at them.

Honey Don’t appeals to both the Marty-types and the Honey-types.

MG and Honey are both stoic lesbians with ample baggage who, independently, offer lots of charm and wit. But together, they collide with such force that whether you’re ogling them as a fetish or lapping up every minute of their on-screen chemistry, it doesn’t matter. Honey Don’t knows that it’s appealing to both the Marty-types and the Honey-types at the same time when Honey and MG get hot and heavy on a barstool, or perform impressive acrobatics at Honey’s place.

The ultimate subversion of Honey Don’t goes beyond its ability to knowingly and willingly appeal to multiple sensibilities. It’s the way that the film combines extensive sexuality with excessive violence. There is probably not another commercial, non-exploitation film that features both a morning-after sudsy sink session and a fully visible slit throat within minutes of each other.

If you come to the film looking for a classic Coen Brothers neo-noir, you’re also going to be faced with overt queer intimacy. If you come to Honey Don’t looking for queer cinema, you’re also going to get Chris Evans in some of the most absurd bedroom scenes you’ll ever see.

The film is absolutely designed for both audiences and finds a way to make sure you enjoy both sides of it, regardless. The gruesome is capped with comedy, the lurid is followed by violence, and everything is always completely sincere.

Honey Don’t is a great piece of queer art.

No, not everything in Honey Don’t works exactly as designed. The final confrontation is a bit too far out of left field for even this film. And for as much as Chris Evans is doing the best version of this character he’s done, he still delivers it a bit more stiffly or too unplayfully to be just right. But the lesser elements are handily overcome by a movie that looks and feels fantastic at every turn.

The visual design for Honey Don’t takes advantage of the rundown, dusty desert by making Honey pop through it at all times. Her car, her lipstick, and her clothes are all bold and bright. It’s impossible not to look Honey’s way, no matter where she is among the rundown buildings and chipped paint signs. The soundtrack also keeps the energy flowing with the film’s brisk pace and short runtime.

Honey Don’t is a splendid subversion of crime dramas and a great piece of queer art. The clues hardly matter, the mystery isn’t the point, and the characters are sincerely big and bold, rather than worn-out reiterations of the typical cops, criminals, and dames. It’s a movie with multiple audiences in mind that knows how to get each of them revved up, twist their genre expectations, and leave them deeply satisfied with the journey.

Honey Don’t is now playing in theaters everywhere.

Honey Don't!

-

Rating - 8.5/108.5/10

TL;DR

Honey Don’t is a splendid subversion of crime dramas and a great piece of queer art. The clues hardly matter, the mystery isn’t the point, and the characters are sincerely big and bold, rather than worn-out reiterations of the typical cops, criminals, and dames.