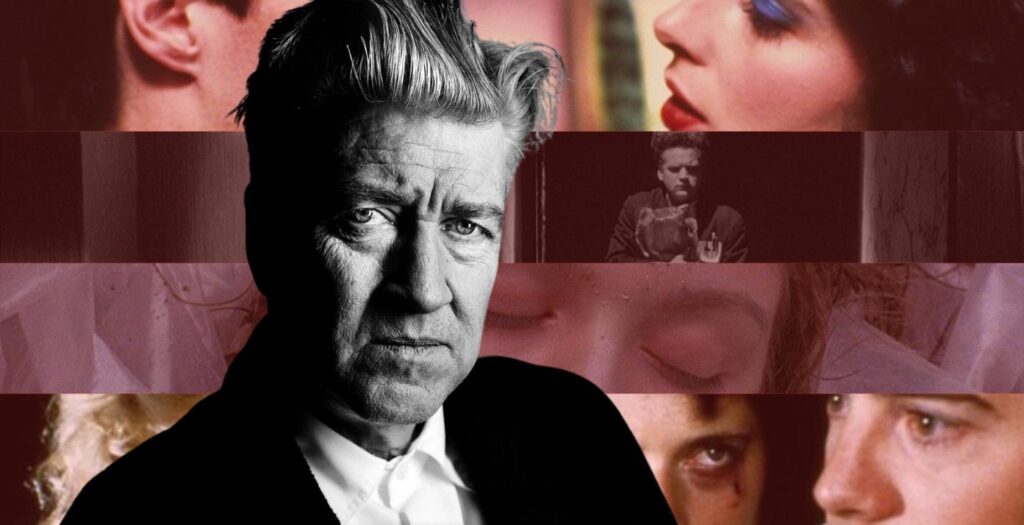

It seems impossible to surmise the immense impact that filmmaker David Lynch had on the world of cinema. Armed with his ephemeral gaze and desire to seek beyond the vanity and veneer of humanity, Lynch sought worlds of wonder that bore immense grief and doused reprehensible ugliness with pockets of hope. His worlds bore universes, refuting the need to answer questions and hold our hands as we traipsed through his tireless dreams and blistering nightmares.

In the short time since his death, I’ve read countless memorials, obituaries, and recollections of Lynch’s influence across the landscape of cinema. Critics who found his work in their teenage years, in their early twenties — early enough that they were formative to their taste and perspectives. I waited. I waited until my late twenties, early thirties, to dig into the world of Lynch because I thought, quite frankly, his work would freak me out.

And it did! But I was ready to sit with that discomforting unease and found catharsis in the oft-utilized depravity that unveiled beauty in unlikely places. Life is miraculous and cruel. It’s absurd and beautiful. David Lynch captures this. His work is ready for you whenever you’re ready for it.

His influence is immeasurable, and he shook off unnecessary constraints that would try to fold cinema into a box, allowing stories to unfold with feverish intent instead. There’s a disquieting discomfort that permeates throughout his best works, offering odd comfort. Perhaps because it showcases the unyielding truth of human nature and the boundless limitations of our existence, both for beauty and cruelty.

There are plenty of words to be shared about David Lynch beyond simply his films and television series. His artistry seeped into every crevice. I’m a fan, hardly an expert. There are works of his I’ve yet to touch out of fear of its ability to inflict anxiety or a day-to-day life that makes catch-up binge-watches difficult.

But the work I’ve seen, consumed, folded into my essence as a critic creates transcendent moments. Life changes you, and Lynch’s work, in its many unpredictable ways, did the same. Lynch was a genuine, singular visionary who refused conformity in his filmmaking. And yet he found universality there and buried deep into our guts and bones.

In writing this, I’ve wrestled with the ‘why’ and the ‘what.’ Why should I add anything when so many have already written so eloquently? What can I add to the conversation when I worry about not knowing enough. So instead, I’m latching on to what I feel, something that Lynch made easy. You can’t a Lynch film feeling nothing. Very often the opposite. Best still, he challenges you to want to know and see more. Here are just five works of his that have left an indomitable mark.

Eraserhead (1977)

There’s plenty of room for argument on what David Lynch film you should watch first, but it should be Eraserhead (coming from someone who began with Mulholland Drive.) The sonic innovation of the film with its bone saw score sound effects makes for a deeply unsettling picture where we experience the sensory overload of a panic attack.

In his first feature film, Lynch shot in black and white, which helps create the persistent sense of unease that dominates the story. Set in a futuristic, desolate, industrial town that ties together the old and new, the film operates in its own universe. Uneasy and grim with truly grotesque special effects, the film works to burrow under our skin and make us experience the simmering claustrophobia of the protagonist.

Blue Velvet (1989)

In every David Lynch project, there’s a moment that renders me breathless. In Eraserhead, it’s when The Lady in the Radiator appears to sing her sickly sweet “In Heaven.” In Mulholland Drive, it’s Rebekah Del Rio‘s aching performance of Roy Orbinson’s “Crying” in “Club Silencio.”

With Blue Velvet, Lynch’s neo-noir mystery thriller, it’s the traumatized innocence of Kyle MacLachlan’s face. Blue Velvet is profound in its disturbance. Vivid and insidious, the underbelly of his world crawls out of the gutters to meet us, even under the vibrant blue skies and white picket fences that can only hide so much.

Twin Peaks (1990)

Full disclosure. I’ve yet to finish Twin Peaks in its entirety as I’ve taken a glacial approach to watching it, dictated by my mood and mental state. Which means I’ve yet to see Fire Walk With Me or The Return. That doesn’t diminish the effect of what I have seen. The palpable grief of the series, aided by the masterful score by Angelo Badalamenti, helps craft the television series’ haunting tone poem. Playfully surreal, it manages exorcize demons while staying light on its feet, even as it questions the sensationalized, voyeuristic impulse to dig into human made horrors.

Mixing soap opera narratives with overtly naturalist performances that create some mesmerizing in its discordance, there’s nothing like Twin Peaks and likely never will be.

The Straight Story (1999)

In his only PG film, Lynch found a new layer to his ability to unravel our greatest vulnerability. The Straight Story, on the surface, is so unlike the rest of his filmography. Distributed by Walt Disney Pictures, the based on a true story drama is another reminder of how much of an actor-director Lynch was. Richard Farnsworth, as Alvin, for all of his medical struggles during the time of the shooting, gives a towering performance as a World War II veteran seeking amends with his brother. Shot in chronological order, The Straight Story finds warmth in suburbia and divinity in the community.

Farnsworth is the film’s heart and soul, which bleeds tenderness and grace despite the requisite off-kilter humor that invades the story. From a shared moment of grief of two old veterans, otherwise left to time despite the youth they sacrificed in the name of their country, to Alvin sharing a campfire with a runaway teenager, empathy sticks to us.

But it’s the climactic moment of Alvin looking at his brother, Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton, who makes an immeasurable impression in mere moments), that truly grasps the core of this story. “Did you ride that thing all the way out here to see me?” Lyle asks. Alvin, empowered and vulnerable, responds, “I did, Lyle.”

Few films affected me the way “The Straight Story” did. Like other pivotal films before it, there’s the me before watching it and the after. Its compassion feels triumphant in the face of other Lynch work as he sought light in oft-forgotten burrows. The story demonstrates the indomitable strength of the human spirit and our desire to right our wrongs, no matter the methods it takes us to reach that resolution.

Mulholland Drive (2001)

We’re not meant to solve Mulholland Drive. At the very least, if there’s a solution at all, we’re not meant to solve it easily. This surrealist drama once more pulls on the neo-noir threads that Lynch so often draws from (Blue Velvet, Lost Highway).

The nightmarish, washed-out portraits of the death of dreams in Hollywood never go the expected route, ending on a note of misery that begs us to start the whole film over to try and pick up on new clues. Naomi Watts and Laura Harring are mesmerizing in dual roles, their relationship oscillating between tender and cold as Betty/Diane tries to find her footing in an unforgiving climate.

Peppered with vignettes that don’t so much derail the main plot as embolden us to dig deeper, the film never loses its cohesive tone. Unnerving and visually divine, capturing the smoke and glitz of L.A., it’s easy to understand why Mulholland Drive is so often an entry point to Lynch. It was mine. And there’s yet to be a singular moment in any of his films that grabbed hold of my heart so fiercely as Rebekah Del Rio’s performance in Club Silencio.

Lynch’s love of music shines through most of his movies, but in her performance “Crying,” you feel that the marriage of music and visuals — the distinctive cinematic playing field — can forever alter you. You don’t forget where you were when you first let those tides of emotions wash over you.

There’s plenty more for those just dipping their toes into the world of David Lynch. Elephant Man is formidable with profound performances. I wasn’t big on Lost Highway, but I understand its merits. More than anything, even the Lynch films not to your taste are worthwhile due to their singularity and creative innovation. Wild at Heart and Inland Empire remain my major blindspots (outside of finishing Twin Peaks), and really, what a blessing.

How lucky is it to have pieces of his legacy left yet unexplored and ready to be seen with eyes anew? By challenging how films could and should be made, David Lynch challenges how we, too, see the world.