Wonder Man is the best superhero origin Marvel has ever made. Not because it’s the loudest, most bombastic, or biggest spectacle, but because it’s clear about what it wants to say and disciplined about how it says it. Instead of treating power as the starting point, the series focuses on something much harder to dramatize: selfhood in a world that constantly asks you to perform.

When Martin Scorsese said Marvel movies weren’t cinema, he wasn’t wrong so much as he was talking about a pattern. Too often, these films prioritize movement over meaning and scale over interiority. The problem has never been superheroes. It’s been how rarely their stories are allowed to slow down and treat human experience as the point rather than the byproduct. Wonder Man is the clearest counterexample Marvel has ever produced.

Across eight carefully paced episodes, Wonder Man uses superhero mythology as a framework for talking about art, labor, trust, and sincerity. It understands that the most dangerous thing about power isn’t what it lets you do, but how quickly other people decide what it should mean. That clarity of purpose is why the series feels confident even when it’s quiet.

Wonder Man takes its time building up both its identity and what it wants to say.

Simon Williams, the series protagonist, is an actor, but the real point of Wonder Man is that Simon is also someone who has spent his entire life adjusting himself to fit the room he’s in. Acting isn’t something he switches on and off. It’s something he’s learned to rely on as protection. The show treats that impulse as survival rather than ambition, especially as Simon works to keep his powers hidden from the world around him.

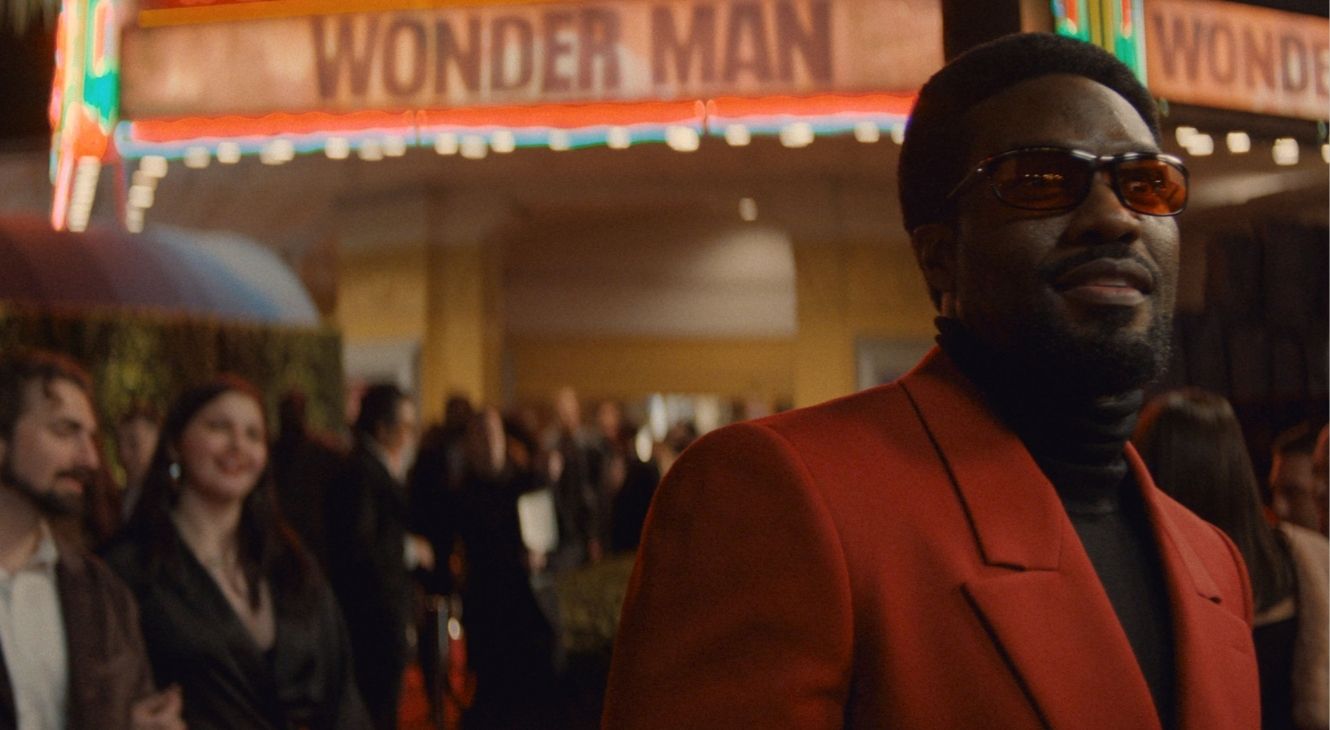

Yahya Abdul-Mateen II makes this feel lived-in rather than studied. His Simon isn’t cartoonishly insecure or exaggerated. He thinks too much, hedges his bets, second-guesses himself, and constantly calibrates how other people see him. Simon doesn’t want fame; he wants authenticity. That tension feeds every choice he makes, both on and off camera.

What makes Abdul-Mateen’s performance stand out is how controlled and precise it is. He can convincingly play a bad performance when the character is supposed to be flailing on a self-tape, then immediately lock in when a scene demands emotional clarity. Just as importantly, he knows when not to perform. The most powerful moments in Wonder Man are the quiet ones, when Simon stops shaping himself for an audience. That’s when the character finally feels grounded, and when the truth of the moment lands without decoration.

Von Kovak, played by Zlatko Burić, is the series’s clearest challenge to superhero convention. His in-universe version of Wonder Man rejects spectacle as the default. He believes superheroes are only worth making when they’re allowed to speak honestly about the human experience. Through him, the show frames its in-universe movie as proof that the genre can still carry weight when it chooses meaning over momentum.

In many superhero stories, powers arrive as destiny. In Wonder Man, they arrive as a consequence. Simon’s abilities are tied to emotional pressure and containment. They don’t offer escape; they expose what’s already there. His strength doesn’t flatten problems; it amplifies them.

As the series unfolds, it becomes clear that Simon’s power isn’t just brute force. He alters momentum, environments, and emotional space. That range mirrors how his psyche has always worked. He didn’t train to be powerful. He trained to adapt. Now that instinct has become physical. The show refuses to frame this as wish fulfillment. Power here is an extension of emotional reality, not a shortcut around it.

Not all power comes as planned. For Simon, it arrives suddenly and is inescapable.

That philosophy carries through one of the season’s most striking choices: an episode built almost entirely around Doorman. In the comics, Doorman has a barely developed origin. Wonder Man gives him one anyway. Not because the audience demands it, but because the story believes it matters. That episode becomes a thesis for the entire series.

The work that makes characters feel real often never appears onscreen. Motivation, backstory, and interior logic still shape every decision. Simon understands this instinctively. It’s how he approaches every role, and it’s how the show approaches its characters.

The series also understands that performance doesn’t begin onstage. Simon’s constant calibration extends beyond acting into how he moves through the world. Wonder Man is attentive to code-switching as lived behavior rather than a concept. Simon adjusts tone, posture, and presence depending on the space he occupies.

Long before he becomes a superhero, he’s learned how to read rooms and survive them. The show recognizes that for people of color, performance often begins before the camera ever turns on, and that pressure doesn’t disappear just because power enters the equation.

Ben Kingsley delivers one of his strongest MCU performances as Trevor Slattery. This isn’t comic relief or a self-aware gag. Trevor understands sincerity and performance equally well as an artist, and he uses that knowledge to position himself as safe. His mentorship of Simon about art, life, and presence is often genuinely insightful. The problem isn’t what he says. It’s why he’s there.

Trevor’s history in the MCU gives his choices real weight, not because he understands power abstractly, but because he’s spent thirteen years trying to outlive a role that never really let him go. When he finally returns to Los Angeles, it isn’t with ambition or a plan. It’s with the hope of a clean slate.

Most people barely remember the Mandarin from Iron Man 3, or never knew who he was in the first place. Some think his role as the terrorist was real. Some know it was a performance. Many don’t care at all. Trevor could almost disappear into that ambiguity if the Department of Damage Control would let him. They don’t.

The return of Trevor Slattery gives Ben Kingsley more room to explore this eccentric character.

What makes the US government‘s involvement especially insidious here is how seamlessly it disguises surveillance as opportunity. Simon believes he’s meeting fellow actors. Peers. People who understand the work. Instead, the room itself becomes a monitoring mechanism. Performance isn’t just expected; it’s observed, cataloged, and evaluated as risk. This isn’t a shocking twist so much as a familiar MCU pattern resurfacing in quieter form

When Trevor agrees to cooperate with the DODC, it isn’t framed as villainy. It’s survival logic. The Sokovia Accords may be gone, but the mindset that produced them never disappeared. Trevor knows how quickly people with power are monitored, managed, and reduced to liabilities. Choosing his own freedom over Simon’s trust reflects experience rather than malice. Here, acting itself becomes compliance. The thing Simon uses to survive is the very thing being used to measure him.

That’s why the betrayal lands so hard. Trevor doesn’t betray Simon by lying about his beliefs. He betrays him by curating the conditions under which trust feels safe. Trevor wasn’t pretending to care. He was pretending about why he was there. That distinction reframes their entire relationship and positions Trevor as something far more unsettling than a traditional antagonist.

Running beneath every relationship in Wonder Man is the same corrosive pressure: money. Not greed in a cartoon sense, but the quiet way economics reframes intention. Trevor’s choice isn’t just betrayal; it’s survival priced against trust. Doorman doesn’t lose himself because he lacks power, but because celebrity adjacency turns that power into currency. Hollywood doesn’t destroy meaning out of malice. It monetizes it. Again and again, the series asks the same question in different forms: what is the price of a soul once money enters the room, and how much art survives the transaction?

One reasn Wonder Man feels richer than most MCU projects is its relationship with art itself. The series is filled with references to Shakespeare, Dr. Strangelove, The Grapes of Wrath, Amadeus, and even Baby’s Day Out. These aren’t Easter eggs designed to reward MCU literacy. They’re part of an ongoing conversation about how art shapes identity and memory. The show treats culture as language, not decoration, for the moment.

That sensibility extends to the cinematography. Wonder Man frequently frames scenes like theater. Static compositions. Long takes. Minimal movement. Often, the only thing shifting in the frame is the actor. These moments slow the viewer down and ask them to watch rather than consume.

How Wonder Man connects with theater and art itself offers much to dissect outside of the MCU.

One of Wonder Man‘s strongest episodes is built almost entirely around absence. Simon doesn’t fight, doesn’t reveal anything, doesn’t escalate. He simply leaves the room during an audition. The show treats that choice with the same gravity that other superhero stories reserve for spectacle, and it works because restraint is the point. It’s an old-school approach that reinforces the show’s belief that performance, at its purest, doesn’t need amplification.

Structurally, Wonder Man feels like Hollywood functioning at its best. Instead of flattening the story into a single dominant voice, the series benefits from multiple directors and perspectives shaping its rhythm. Showrunner Andrew Guest anchors the series with a strong character-first foundation. His background in ensemble-driven television shows is how the series prioritizes conversation, conflict, and emotional rhythm over constant momentum. The scripts never rush past discomfort, and they’re willing to let scenes breathe, which is essential for a story so invested in the authenticity of performance.

That grounding allows directors like Destin Daniel Cretton, Tiffany Johnson, James Ponsoldt, and Stella Meghie to bring distinct sensibilities to different stretches of the season. Cretton’s episodes lean into empathy and restraint, reinforcing the idea that power is emotional before it is physical. Johnson’s direction sharpens the show’s sense of tension and observation. Ponsoldt emphasizes intimacy and social awkwardness. Meghie’s episodes give Simon’s interior struggle an external context that feels lived-in rather than symbolic.

That collaborative structure mirrors the series’ argument about meaning itself. No single voice owns the truth. Identity is shaped through proximity, context, and community. Wonder Man practices what it preaches by letting those perspectives coexist rather than compete.

The in-universe Wonder Man movie succeeds. It’s popular. It works. But it’s still not as moving as the version that almost existed. That contrast underscores the show’s quiet thesis: blockbuster storytelling can have depth when it trusts character over efficiency. Television gives Wonder Man the space to sit with the consequences instead of smoothing them away.

One of the series’ most affecting realizations is that the people closest to Simon were never the threat. His family understood. His ex-partner understood. They kept his secret not out of fear, but out of care. The danger comes from those who see Simon as proof of something larger than himself. Being seen without agency becomes another form of erasure.

Simon is still coming into his own, but he’s one step closer and a reminder that identity is in flux.

By the end of the season, Simon has power, visibility, and choice, but his origin isn’t finished. His true self is still emerging. That incompleteness is the point and the reason to continue. Identity isn’t unlocked all at once, especially for someone who has spent a lifetime performing to survive.

Wonder Man isn’t about explosions or scale. It’s about what happens when someone with immense potential stops performing long enough to be seen. Simon doesn’t become a hero because he discovers his power. He becomes one by choosing sincerity in a world that constantly demands performance.

The series keeps asking what superheroes can teach us. Wonder Man answers by refusing easy lessons. Heroes matter when they reflect how people live, adapt, and grow. Simon still has more to learn, and that openness is the story’s final strength rather than a loose end.

Ultimately, Wonder Man makes a simple, convincing case for why superhero stories still belong in cinema. When these stories slow down, trust performance, and center human experience over spectacle, they do more than entertain. They observe, interrogate, and endure. That’s not just good Marvel. That’s cinema.

Wonder Man is streaming now on Disney+.

Wonder Man

-

Rating - 10/1010/10

TL;DR

Ultimately, Wonder Man Season One makes a simple, convincing case for why superhero stories still belong in cinema.