Created by Vince Gilligan, Pluribus follows a world reshaped by a sudden, unexplained end to human violence, forcing long-standing systems of control over land, animals, and one another to break down. Rather than focusing on spectacle or technical answers, the series tracks how people respond when human dominance is no longer the organizing principle of daily life.

Through Carol (Rhea Seehorn), a writer grappling with personal loss and a rapidly changing world, Pluribus stages its questions not through grand declarations but through repeated encounters with environments that no longer behave according to human expectations.

Throughout Pluribus season one, Carol is in front of landscapes she doesn’t know how to read. The show never pauses to explain this to her, and it doesn’t reward her for missing it. A bison stands on a golf course in Albuquerque. Wolves move through neighborhoods.

The Plains open up under an uninterrupted sky. These moments are not background details or symbolic Easter eggs layered on top of the story. They function as the text of the show itself, and Carol continues to move past them without engaging with what they represent.

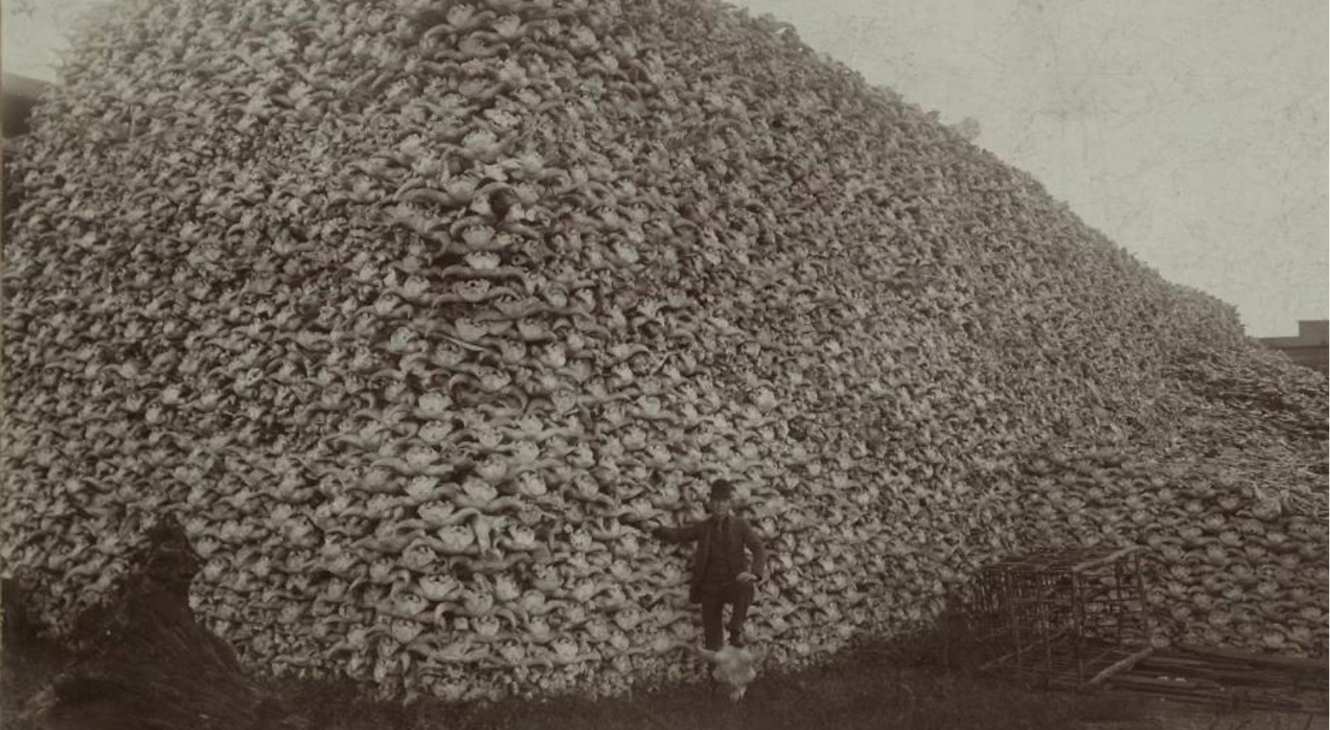

Before the nineteenth century, historians estimate that between 30 and 60 million bison lived across North America. Plains Indigenous nations lived alongside them for at least ten thousand years without collapsing the system.

The animals shaped grasslands, fertilized soil, supported food webs, and sustained human life without being driven toward extinction. The land functioned because the bison were part of it, not because they were controlled or managed into submission. That balance ended through deliberate policy.

The symbol of the bison and its loaded significance in history looms large in Pluribus.

By the mid-1800s, the United States government understood that bison were the foundation of Plains life. Military leadership recognized that destroying the animals would collapse Indigenous resistance without requiring prolonged warfare, and this logic was not hidden or inferred. It was stated openly and acted upon.

In 1867, General Philip Sheridan praised commercial bison hunters before the Texas legislature, stating that they had “done more in the last two years to settle the Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last thirty years,” because they were “destroying the Indians’ commissary.” He urged lawmakers to let hunters “kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo are exterminated,” framing mass slaughter as a path to stability and peace.

Railroads made this strategy possible at scale. As rail lines expanded across the Plains in the 1860s and 1870s, trains carried hunters west and hauled hides, tongues, and bones east. Most carcasses were left to rot after the skins were stripped. Later, bison bones were collected and shipped by rail to be ground into fertilizer. By 1883, fewer than one thousand bison remained.

Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano opposed efforts to protect the animals in 1872, arguing that their disappearance would “remove the principal obstacle to the civilization of the Indian.” The objective was starvation through environmental destruction, carried out as federal policy rather than accident or oversight. That history appears quietly in Pluribus on a golf course.

A golf course does not exist by accident. It requires land clearing, irrigation, fertilizer, and constant maintenance, replacing native systems with leisure infrastructure. Seeing an American bison there is not a charming image of wildlife returning. It is a collision between what the land once supported and what it was reshaped to serve, a reminder of how thoroughly the environment was reorganized around human comfort. Carol does not stop to absorb that collision. She keeps driving.

Later, Pluribus offers another moment during an open-plane shot over the Plains. Carol looks out at the land and fixates on the train cutting through it. She calls the horn the loneliest sound in the world and admits that she loves it, emphasizing that she has never told anyone this before. The sound becomes a private confession rather than an opening into the history beneath her.

Carol’s interactions with nature reflect human behavior, how it hopes to shape it and what it refuses to accept.

When she realizes the train is transporting food, irritation sets in immediately. Knowing that the Hive sustains itself through processed human bodies, she jumps to that association without asking what the train carries beyond that fraction, who it feeds, or what systems keep billions of people alive without killing them directly. The moment collapses inward, filtered through suspicion instead of scale.

That narrowing matters because the train represents the same infrastructure that reshaped the Plains in the first place. Rail lines did not merely connect cities or move supplies. They enabled industrial-scale extraction and killing. Before railroads, even running bison herds off cliffs did not destabilize the population. Industrial transport did. Trains carried hunters west, hauled hides and bones east, and finished what federal policy had already set in motion.

Carol centers the moment on her own sense of isolation rather than the history embedded in the land. She ignores the wolves she heard earlier in the season and treats the Plains as scenery instead of consequence. This is consistent with how she responds to the world throughout Pluribus, registering personal discomfort while bypassing the systems that produced it.

Carol wants to preserve objects rather than systems. She focuses on paintings, museums, and personal memory. When animals move freely, and human structures loosen, she experiences discomfort. When human control recedes, she perceives loss. She never seriously engages with the possibility that the planet might function better without constant management.

This is why the bison matters in Pluribus, and why the show keeps returning to it visually and thematically. The bison is not a symbol of wilderness or nostalgia. It is living history. Its near-extinction followed deliberate human action meant to clear land, erase Indigenous life, and make expansion easier. Its reappearance forces a confrontation with what that process actually looked like when it was successful.

Pluribus season one reinforces this idea elsewhere in quieter ways. When Manousos (Carlos-Manuel Vesga) challenges Carol by asking whether it is ethical to value an ant as much as a human, the question is not meant to provoke a debate over a moral hierarchy. It is meant to expose how perspective shifts when scale changes. From a certain vantage point, individual distinction collapses. Systems matter more than singular lives. Damage is measured by impact, not intent. Carol never seriously entertains that shift.

Action enforces change, making the abstract into something tangible and real. The bison’s return heralds this.

She worries about animals entering museums. She worries about art being damaged. She worries about food transport without accounting for how food systems already function at the planetary scale. She reacts to the idea of humans being processed by the Hive without ever reconciling that tens of billions of animals are killed each year to sustain human comfort. The concern is always framed around what feels wrong to her, not what has already been normalized.

Whether the Hive is understood as a caretaker, a regulator, or something closer to an experimenter, the underlying logic remains consistent. Human expansion and technological advancement have always come at the expense of the land.

Railroads, industrial agriculture, global trade, and extraction-based economies did not arise alongside ecological balance. They replaced it. Someone looking at Earth from far enough away would not see innovation, but the disruption humans have caused. From that perspective, humanity is not unique. It is invasive.

That does not make the show anti-human, nor does it turn the bison comparison into a moral accusation. It reframes the question entirely. The issue is not whether humans deserve to survive, but whether survival must always be defined by domination, expansion, and consumption. The bison did not get a say when those rules were applied to them. Humans now struggle with the same loss of agency.

Seeing ourselves as the bison changes how Pluribus reads. The signal no longer feels like an attack or a punishment, but an intervention; a limit imposed after damage crossed a threshold. Not because humans are evil, but because unchecked systems eventually destroy what sustains them.

Carol cannot sit with that possibility. She keeps centering herself, her grief, her discomfort, and her need for control. She preserves objects while ignoring systems. She hears loneliness where there is history and sees loss where there is recovery. Time and again, Pluribus places her in front of the evidence and lets her walk past it.

The bison does not walk past us. It stands there, on land reshaped for leisure, asking whether we recognize what happened when one species decided it was entitled to everything. And whether, when the roles begin to reverse, we can see ourselves clearly enough to understand why the signal was sent in the first place.