Gore Verbinski is one of our finest filmmakers. He is one of extremely few people to have made a successful English-language remake of a Japanese movie in The Ring, the director of the best live-action Bioshock movie (even if A Cure for Wellness isn’t technically a Bioshock movie) and one of the best animated movies of the past 15 years in Rango, and also the guy who gave us three spectacular gonzo blockbusters in the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy.

Although perhaps best known for his work in huge blockbusters with multi-million-dollar budgets and extensive special effects, Gore knows how to do a lot with a little, as seen in his earlier films, such as Mouse Hunt. For his triumphant return to cinema after nearly 15 years, Verbinski returns to his roots with a small-scale, low-budget movie that nevertheless feels as big as his blockbuster efforts. It is also a movie that takes on a topical subject, with a sci-fi comedy that is proudly anti-AI.

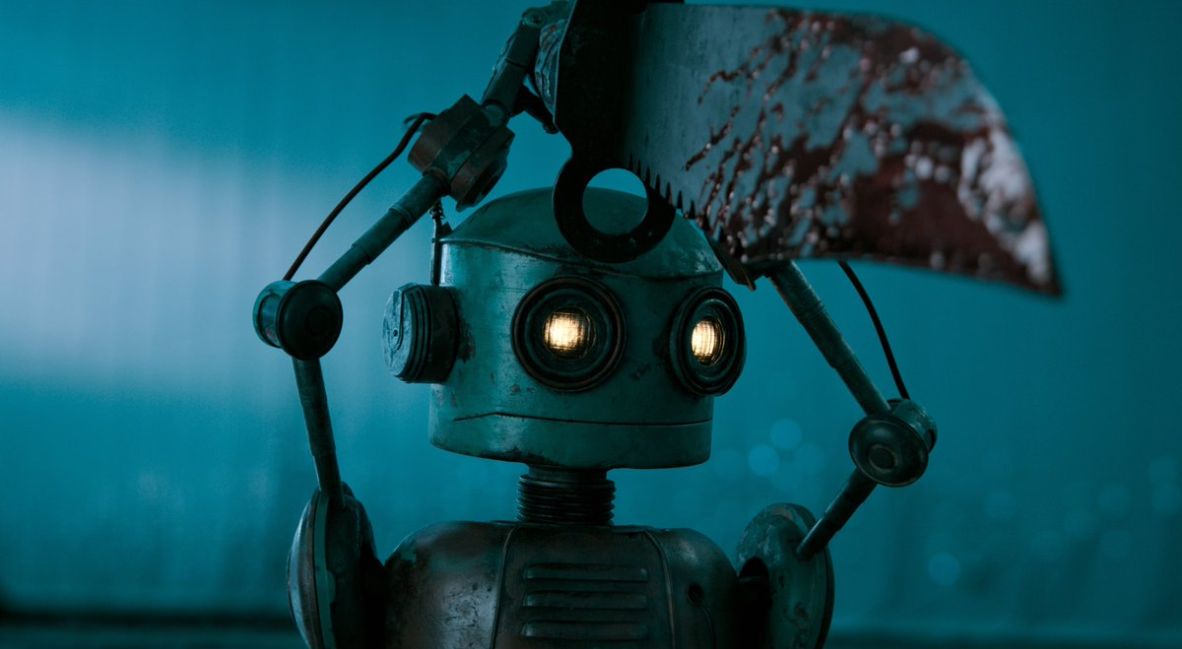

Good Luck Have Fun Don’t Die is Gore Verbinski’s solid stance against AI.

Good Luck Have Fun Don’t Die follows a homeless-looking man (played by Sam Rockwell) who claims to be from the future and stops at a diner to recruit people to help him save the world from an AI threat. It is a movie with a stellar ensemble cast, a hysterically funny movie that is also quite provocative in what it says about not just AI but social media and even the current school shooting crisis. It is Verbinski’s most ambitious film in years, and his funniest yet.

Following the movie’s surprise premiere at Fantastic Fest, we got to sit down with Gore Verbinski to talk about the making of Good Luck Have Fun Don’t Die, his views on AI, and why CGI has declined in quality over the last decade.

BUT WHY THO: This movie is quite unequivocally about the threat of AI, but you also spend a lot of time showing how social media has impacted us negatively. Why was that idea important for you in relation to this story about a rogue AI?

GORE VERBINSKI: I think that’s the beginning of the erosion. This man from the future is coming back to save the world, but save the world from what? I think that is the primary sickness that allows the other one to manifest. I think the fundamental origins of AI seem to have been focused on what’s your user profile, or how are we going to keep you engaged, or how are we going to know what you buy, what you think, how we’re studying humans and using language.

So it seems like that AI version one is sort of been studying us and studying what we like and what we hate to keep us engaged. So that sort of doom scrolling aspect I think it’s fascinating, and because it’s been studying us for a while prior to becoming sentient, then sort of hardwired into its source code is probably all of our flaws. So I think that social media and phones are where we started not talking to each other.

BUT WHY THO: Something I admire about your approach to filmmaking is how you make things feel and look bigger. This movie is clearly not as big budget or scale-wise as some of your previous work, but it nevertheless feels spectacular. How do you make a relatively small-scale story like this feel big?

GORE VERBINSKI: I think this whole film cost the price of David Jones’ tentacles. I mentioned Repo Man as a big inspiration because that felt like a movie where it didn’t feel like they asked for permission; it felt like they just went and made it with what they had and put some smoke and some boots by the side of the road. It was incredibly low-flying.

I think this film is sort of a twisting taffy, so it starts very loose and kind of real and honest at the diner, something like Dog Day Afternoon, and then it twists towards Akira at the end. You start analog, you end up digital, you start looser, you end up a little more composed. I think there’s things in Akira I still don’t understand. The last 20 minutes of the movie, I’m like, what the fuck. So, trying to keep things enigmatic when it becomes visually enigmatic.

BUT WHY THO: Akira is one of my favorite movies so I have to ask you, as you mention having this enigmatic aspect to the story, how do you find the right balance of leaving things unsaid while still exploring the larger world of this film?

GORE VERBINSKI: I think it’s important that Sam Rockwell’s character remains a sort of untrustworthy narrator. When he walks into the diner, you have to dismiss him as a vagrant who climbed out of a dumpster, who maybe studied Shakespeare at one point in his life, but ended up delusional and needs to be institutionalized.

Then, slowly in that opening, it’s tough to start your movie with an 11-page monologue. It’s a very tough thing to do. So getting that to sort of convince us to go on the ride with him, even though we’re not 100% sure if he’s telling the truth. I think keeping him untrustworthy kind of keeps you off balance in a fun way.

BUT WHY THO: Something I was curious watching the movie is that you portray a lot of AI slop, but you have said you didn’t use any AI in the making of the film. Was there a conversation about using AI in order to show how bad it is or was it always the intention to avoid it?

GORE VERBINSKI: I think all of that was done two years ago, so you were just beginning to maybe be able to do things in this world, but no real emotion, right? So some stuff was licensed from people, from creators who created stuff in animation, but not specifically AI. We had to kind of future-proof it, so we had to really know what’s coming, like, pretty soon, you’re going to be able to just ask it to animate something. We weren’t able to do that.

There were two factors. One was trying to think about what’s coming, and how we could not be immediately dated, meaning we had to kind of leap forward and create animations that would feel like something that you could ask AI to do.

Then there was, legally, they wouldn’t allow us to use AI because we were still at that dubious place where you’re not sure if you use AI to make something, it could be using a picture that’s Mickey Mouse’s ear or something. So there were strict rules about not using AI, which I think was good, but those are going to be eroded very quickly.

BUT WHY THO: The movie leaves some things up for interpretation, playing with the idea of a simulation and AI just showing the characters what they want to see, did you at one point thought of giving a direct answer or was ambiguity always the plan?

GORE VERBINSKI: That’s certainly a lot to do with it; it’s very hard to make a movie made now because everybody wants a franchise, but nobody wants to make a franchise, nobody wants to start off, they want to just jump into number five of some pre-existing IP or rely on a sort of algorithmic enslavement streamer.

But I think there’s a lot more of a story to tell with these guys in terms of answering those questions and sort of letting them kind of breathe. Plus, he’s on this hundred and eighteenth journey when the film ends and there’s all sorts of possibilities, so I’d like to encourage our kind of champions to get enthusiastic about that.

BUT WHY THO: You mentioned the film having a low budget compared to some of your previous movies, but I wanted to ask about the experience of working with your VFX team because there are a lot of spectacular moments in the film and a very Akira-esque final act.

GORE VERBINSKI: It was really difficult, I gotta say. We had Jessica Norman at Ghost VFX, who is really a great small visual effects company. I actually called my friend Hal Hickel at ILM and told him about the movie. I said there’s no way you guys can do this, and he said no, we couldn’t, but he recommended this company called Ghost, which they occasionally use to pick up some shots on Star Wars stuff, so I knew they were quality.

I looked at their work, they were a small house out of Europe, and so we kind of went to them and said, here’s every penny we have. And they loved the script, they were passionate about the project, they said, we’re gonna make it work.

It was a different approach than a normal visual effects process, because we didn’t have a visual effects editor. You usually have a visual effects editor or a visual effects department, a whole team. But here everybody had to do six jobs, both on our end and theirs, and we’re sharing ideas and sketches from the very start of the process, which made it a very close collaboration.

BUT WHY THO: On that note, my last question for you is about the state of VFX. You’re a name that always comes up in conversation when people talk about VFX done right, so I’m curious if you have an opinion on what makes visual effects work in movies and how the look of them has changed in the past 15 years, even as movies become more reliant on them. Why don’t they look as good, essentially?

GORE VERBINSKI: I think the simplest answer is you’ve seen the Unreal gaming engine enter the visual effects landscape. So it used to be a divide, with Unreal Engine being very good at video games, but then people started thinking maybe movies can also use Unreal for finished visual effects. So you have this sort of gaming aesthetic entering the world of cinema.

I think that’s why those Kubrick movies still hold up, because they were shooting miniatures and paintings, and now you’ve got this different aesthetic. It works with Marvel movies where you kind of know you’re in a heightened, unrealistic reality. I think it doesn’t work from a strictly photo-real standpoint.

I just don’t think it takes light the same way; I don’t think it fundamentally reacts to subsurface, scattering, and how light hits skin and reflects in the same way. So that’s how you get this uncanny valley when you come to creature animation, a lot of in-betweening is done for speed instead of being done by hand.

And then just what’s become acceptable from an executive standpoint, where they think no one will care that the ships in the ocean look like they’re not on the water. In the first Pirates movie, we were actually going out to sea and getting on a boat.

I think in Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die, we try to be really strict with making at least 50% of the frame photographic. I think that keeps you honest. You can use props as a reference, and when you see the CG replacement, you know how to replicate the real thing.

I think that Unreal Engine coming in and replacing Maya as a sort of fundamental is the greatest slip backwards. And there’s also something, a mistake I think people make all the time on visual effects. You can make a very real helicopter. But as soon as it flies wrong, your brain knows it’s not real. It has to earn every turn; it has to move right. It’s still animation, sometimes it’s not just the lighting and the photography, sometimes it’s the motion.

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die will be released in theaters on January 30, 2026.