It’s hard for Riftbound: League of Legends Trading Card Game not to feel a little inevitable. League of Legends, the MOBA game made and published by Riot Games, has grown year-over-year from just one game to a wide umbrella, encompassing everything from spin-off games to a lauded animated series on Netflix. A physical card game makes natural sense.

This isn’t the first time Riot Games has dabbled in the physical space; the publisher has produced tabletop games like Mechs vs. Minions and Tellstones. With Riftbound, though, Riot enters a card game space where titans like Magic: The Gathering and Pokémon reign. Vying for attention there isn’t easy, even with the recognition League of Legends has garnered over a decade-plus.

At PAX East 2025, I sat down with Riot’s Game Director for Riftbound, Dave Guskin, and got to run through a couple of games, seeing the demo decks for four very recognizable champions: Jinx, Viktor, Volibear, and Yasuo. Alongside each deck’s signature champion, other champions were lurking in the decks, including two versions of Miss Fortune, Kayn, and alternate versions of the main champions.

Guskin tells me the team sought a mix of champions for Riftbound, trying to incorporate new and old, with characters made popular by Arcane and those from the original 40 champions.

“I think in general, we found a pretty good mix for the first set,” said Guskin. “I think over time, what we’ll probably end up doing is bringing in more fan-favorites, bringing in ones that maybe, you know, take a new look at this in a different context, to try it out.”

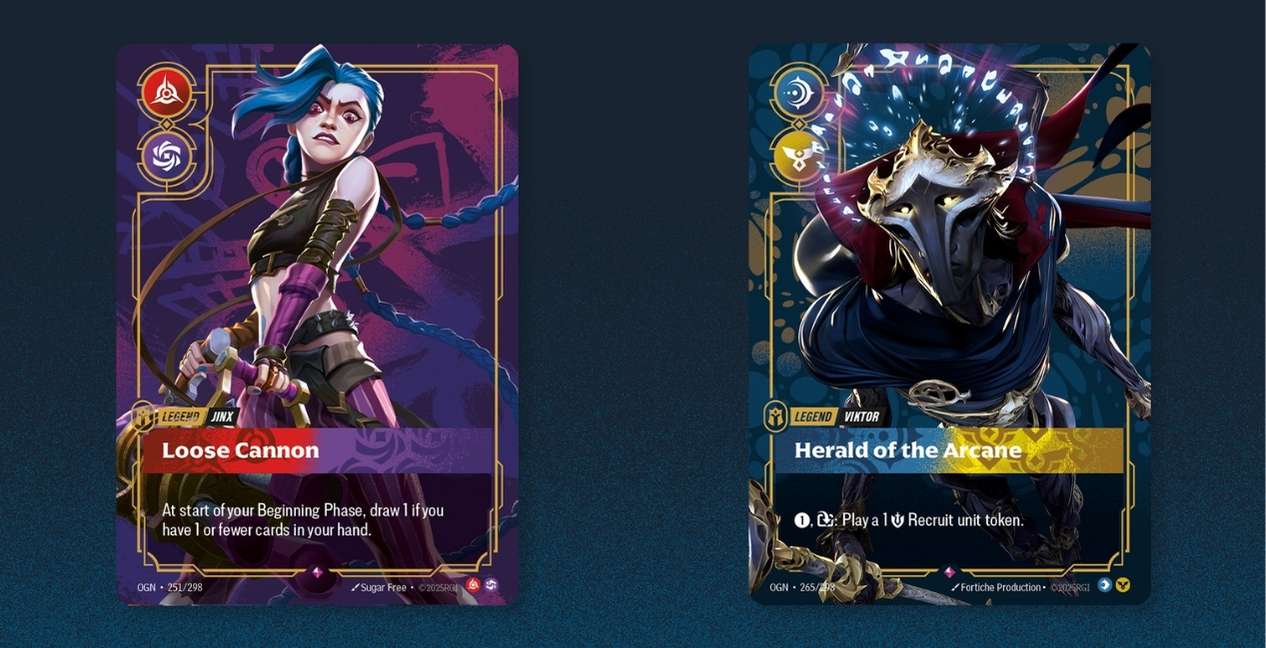

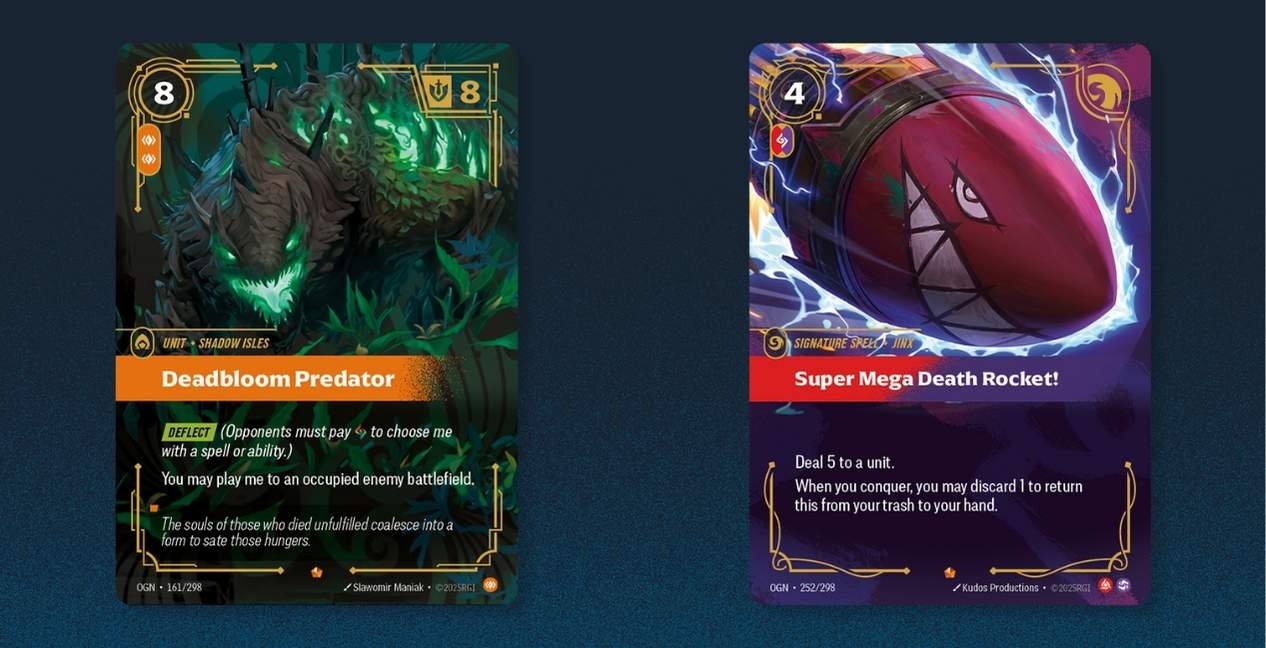

Riftbound makes sure to adapt its Champions as characters to color archetypes to fit their personalities.

The champions and cards fall into archetypes denoted by color. Red is aggressive, which fits a particular Jinx card that gains damage when she attacks. Yellow, meanwhile, likes to go wide and build up a tidal wave of bodies, which suits Viktor’s tendencies for proliferation.

The core mechanic, and what feels like it will separate Riftbound from other big games, is its battlefields. Rather than punching each other in the face to reduce a life total to zero, players in Riftbound summon units into their base. While they still have a turn of tapped summoning sickness, once they can act, they mobilize towards battlefields. Capturing a zone, or holding one at the start of a turn, earns a point, and first to 8 points while ending the turn with both battlefields held wins.

It’s a subtle difference, reminiscent of Marvel Snap, that made a huge difference. There’s still combat, as minions, champions, and even small armies of tokens slam into each other, but it’s all in pursuit of battlefield control. Not only does taking a battlefield area give you points, but it also proffers the bonus of whatever battlefield card is there. That might mean an additional Rune resource you can draw each turn, or the ability to pull a unit back during any attack. In one game, I could use this retreat tactic to constantly bait and strike my opponent’s units, without losing an important card in the process.

Mobility, and letting cards move around the board, makes Riftbound feel active the way that Summoner’s Rift in League of Legends does. It’s an intentional effect, as Guskin tells me.

“We want people who are coming in, who know these champions and care about the identity, and even the way they play in [League of Legends on PC], to be something that they feel okay, it’s kind of reminiscent of that, so where possible we did do that,” said Guskin. “But of course, it’s like, a different game system. Card games don’t have, you know, a jungle with bushes and XP and levels.

“There’s only so many ways we could represent that,” Guskin continued. “So we’re not like, a 100% true, exactly one-to-one translation, but where possible, we tried to find TCG mechanics that were good representations of the feel and experience of [League of Legends].”

Guskin refers to “hidden,” a trap mechanic in the Viktor deck I played. (I didn’t get to draw into Teemo, sadly.) It allows Teemo to unexpectedly strike enemies, mirroring the way a Teemo in League of Legends might hide in a bush and wait, biding his time until he can ruin your day.

Riot Games is translating its digital champions into analog playspaces.

Champion identities help with this, too. While each deck can have various League of Legends champions, one gets named as your specific champion; you start with one out of your deck, able to be played as soon as you can afford them, and you can have another two copies in the deck. It feels a little similar to a Commander in Magic, but once these cards go down, they’re down and out, and you’ll need to draw another one before you can put their physical presence back on the field.

Even without that, though, you also have “legend,” which is an ability that can either passively enhance your gameplay or add a special active ability, which ends up being playstyle-defining. Jinx’s legend, for example, lets you draw two cards instead of one if you start a turn with one or fewer cards in your hand. It sets up the aggressive fire-reload-fire playstyle of the Purple-Red Jinx deck and feels very in-tune with her gameplay style. Viktor, meanwhile, can spend some extra resources to generate token creatures, further fueling his glorious mechanical revolution.

Keywords like “Ganking,” a reference to a broad MOBA term where a player tries to head over to another lane and take out the opposing player holding it down, and you can start to see how League’s ideas helped provide a framework for the card game. In Riftbound, ganking means a character can move between zones, rather than having to return to your base and then re-deploy. It’s mechanically interesting, and also feels thematically consistent with characters like Vi.

There is the digital question, though, and it’s an especially interesting one considering Riot Games already has a digital card game with Legends of Runeterra. Guskin led the Runeterra project for several years before Riftbound, and notes that one of the avenues Riftbound draws from for art—alongside League of Legends, Wild Rift, Arcane, and brand-new art—is Legends of Runeterra. There is a difference in direction, though, between Runeterra and Riftbound.

“For Riftbound, we think of it as like, an in-person social experience first,” said Guskin. “That’s why we built it from the ground up to be multiplayer, we built it so that you can have a lot of really interesting deck-building and collection decisions. And so that’s kind of the core focus.”

The physical-versus-digital seems to be the big delineation, alongside Legends of Runeterra’s lean towards PvE experiences. Riftbound, on the other hand, really seems to lean into the tabletop angle. While I only played one-on-one duels, Guskin and the team told me about rulesets for four-player free-for-all and two-on-two team battles. All of these could use the same basic structures and core concepts, and your 40-card deck can slot right in for any of the modes mentioned above, too.

“When you build a deck, it’s viable in any of the formats you can play in,” Guskin tells me. “You can play it in 1v1, you can play it in free-for-all multiplayer, you can play it in 2v2.”

But, how does Riftbound plan balance collecting versus playing?

As a trading card game, though, with booster packs and decks in the works, there is always the question of how Riot Games plans to balance the goals of its sets. Card games can be big draws for players, but also collectors, especially if there are highly sought-after cards; you can see the way Pokémon packs can’t seem to lie still on a store shelf, and wonder if Riftbound might capture similar attention.

When I asked Guskin about how the team is thinking about the collecting-versus-playing dynamic. He told me the split is 50-50 but leaning towards play.

“In terms of long-term audience, I’m hoping it’ll be just as good for players as it is for collectors,” said Guskin. “But when we start the game, I think it’ll be like, we’ll show the promise and the possibilities of the collector side of things, but we won’t have fully rolled that out yet.”

There are certainly more questions to answer for Riftbound moving forward, but after spending an hour sitting and playing with the decks, it was a game I kept thinking about and wanting to play again throughout the weekend. Riftbound feels similar enough to League, but different enough that it was hard to scratch the same itch with any other card game I could jump into.

Riftbound’s first set, Origins, this summer in China and later on in several English-speaking countries in October 2025.