It is often said that those who do not study history are doomed to repeat it. In the Assassin’s Creed franchise, history may be editorialized, but the broad strokes of power, dominance, and the perpetual cycles of violence they bear are based on rigorous research and generally accurate recounting. For all of Assassin’s Creed history, the franchise has put players, readers, and viewers in the shoes of Assassins whose people, community, culture, country, and/or religion are under siege from an invading force. Be it the indigenous peoples of the Lavant under siege from Crusaders in the original Assassin’s Creed, the British rule over the American colonies and the altogether terror over Native Americans in Assassin’s Creed III, or the Roman conquest over Ptolemaic Egypt in Assassin’s Creed: Origins, the series main characters have always fought back against oppressive, colonizing, and otherwise evil forces. Until Assassin’s Creed Valhalla.

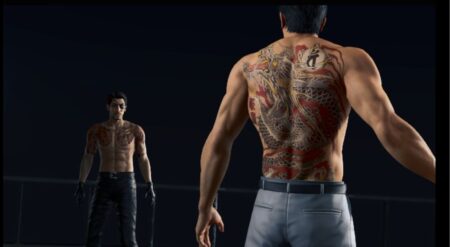

Assassin’s Creed Valhalla marks the first time in the series’ history where you play as the invading force. Eivor, Sigurd, and the rest of your clan are not refugees seeking a safe place to practice their religion. They’re not wanderers or seekers of knowledge simply exploring new places and peoples. They’re Vikings. Their objective is to raid and pillage and establish a kingdom of their own. They are perhaps political refugees in a way, escaping their fathers’ kingdom in order to establish a place where they can hold their own power the way they want it to be held. But even still, the Ravensthorpe landing party is a foreign conquering force who throughout the game join arms with other Danish, Norse, and occasionally Anglo-Saxon factions in an attempt to gain political and military power across the whole of England.

The game may put Eivor in a slightly kinder position, seemingly more interested in simply carving a haven for her people in this new land than in conquering England. But history shows that the invading Vikings of the 9th Century were a bit more interested in domination over England as they warred against King Aelfred than Eivor was in the game. And playing as the people on the other side of a power dynamic between invading and invaded peoples seriously complicates the moral positions of the series.

Assassin’s Creed, at its core, is about the triumph of free will, even if that freedom means moral wrongs, over a society controlled and determined by essentially autocratic holders of power, even if they have the best of intentions. In Valhalla, this struggle is the same as ever: Eivor and the Danes fight for the freedom to control their own destinies as non-Christians and non-Anglo-Saxons whereas Aelfred is fighting for dominance over all of England and all of its inhabitants, Christain, Danish, or otherwise.

There lies the first layer of complexity. The Anglo-Saxons were in England first. So what right do the Vikings have to invade this land and demand not to be ruled by their king? And the game does a good job sympathizing with the English crown as it displays Aelfred as a righteous and likable ruler, despite the cruelties imparted during their war. Yet, the game does not take place in a historical vacuum. The game is explicit at times about the cruelties of the Anglo-Saxons against the Picts and the Welsh or the Christian Irish against the Druids in the “Wrath of the Druids” DLC. These Indigenous people lived in England and Ireland long before the Anglo-Saxons, long before Christianity, and even long before the Roman invaders from the previous millennium whose ghosts are strewn throughout the game. The Christian hegemony of 9th Century England is itself a colonizing force, just as well as the British Empire of the next millennium has been a dominant colonial force for centuries.

It’s colonization all the way down in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla. There isn’t any attempt to sugarcoat or justify it. The franchise has always been clear that oppression—physical, religious, cultural, and otherwise—is inherently evil and wrong. So why play as the conquering force? Other than because Norse mythology is rich and interesting and being a Viking is cool, of course. Why not play as one of the Indigenous peoples whose sovereignty and every way of life has been under threat from endless factions over thousands of years? I think, in part at least, that the answer is that because as we study history, and as we reconcile with how power dynamics and oppression continue to take shape in and shape the future of the world today, we have to understand that power ultimately perpetuates reciprocating cycles of violence. While it’s easy, and generally proper, to place different groups into either the box of the oppressor or the oppressed, sometimes, different groups fall into a different box at different times depending on how power dynamics have shifted and are playing out at a given point in history.

Playing as Eivor in this game, you empathize with the way her people have been subjugated by other Norse powers in their homeland and by the Anglo-Saxons upon their arrival in England. But at the same time, you bear witness to and participate in the armed oppression of native peoples throughout England and ultimately come to respect the leader of those oppressive forces in the way of King Aelfred. It’s a microcosm of just how complicated and deeply uncomfortable it is to be human and contain such polar multitudes. Yet, it all happened in the real world, and rather than either glorifying it, justifying it, or ignoring it, we can and must reconcile with the horrors of reality and actively choose to learn from history’s wrongdoings and do better by all peoples, lest we be doomed to repeat them.

Spoilers for “Wrath of the Druids Below”

Spoilers for “Wrath of the Druids Below”

“Wrath of the Druids” exemplifies the totality of this axiom better than any Assassin’s Creed story. In this DLC, Eivor travels to Ireland at the behest of her cousin Bárid who has recently become the king of Dublin. Dublin is a Danish city. Bárid’s father was its king before him, but the Christian Irish fought many wars over the previous decades to squash Danish incursion into Ireland and left Dublin in shambles. Bárid is committed to and loved by his people though. He has converted to Christianity in order to help win the support of the new High King Flann Sinna while retaining his Norse identity as well. And now, together with Eivor, the two are keen on supporting Sinna in conquering the country and ruling truly as the sole sovereign.

But there’s a catch. Christianity is an imported religion in Ireland, and to truly subdue all of Ireland’s people means to also subdue its indigenous peoples, chiefly in this DLC, the Druids. The chief conflict truly of “Wrath of the Druids,” for perhaps the first time in Assassin’s Creed history, is stopping an armed and radical band of Druids from accumulating more power and ensuring they never have the means to usurp the High King’s throne and rule. Many of the game’s Druid allies make it clear that this faction, the Children of Danu, do not represent their whole people. This subsect is a menace they would prefer obliterated as well; if only they would be left in peace at the war’s end.

Of course, no matter Eivor and company’s promises, the petty kings of Ireland are bent on convincing Sinna to launch an inquisition against all Druids, purging them entirely from their land so that Christian Irish need not worry about splinter factions emerging in the future. They, of course, neglect to chastise the other minority groups in the room, namely the Danes, but you get the sense that, like Aelfred in the base game before them, they see Danish assimilation into Christianity as the inevitable conclusion of that plot thread (and history would prove them right). Fortunately, Eivor and Sinna prevent the inquisition, but history tells us that the Druids were subject to awful violence and ethnic cleansing, eventually disappearing from history altogether.

It’s a dark ending, and on the surface, can feel pretty Nialhistic. One might ask, what is the point of striving to protect oppressed peoples when the oppressors are inevitably better armed, endlessly persistent, and often outnumber the oppressed? Eivor may have staved off a mass slaughtering of Druids, but she departs Ireland having to participate in the irreversible destruction of Druid life and culture. Frankly, in a quest to help create an Ireland where self-determination for all people can be possible, she has only ended up upholding a power structure that would see all of its subjects determined towards their Christian hegemony.

What is the point of free will when independence so easily falls to the might of a singular and oppressive deterministic power? Might the Templars be right that even if so often the wielders of power wield it for selfishness and evil, the world requires order to ensure the maelstrom of free peoples can never do some greater harm than that which the powers that be consider the necessary threshold for maintaining peace and prosperity?

Of course not. The Templar world vision is how we get social and economic stratification so bad that people live unhoused while others horde endless wealth. It’s how monopolies of state violence are used as justification for quelling righteous protests against those powers. The Assassin’s world vision of a society, where it is the people’s burden to make mistakes rather than that of a singular institution of power, is the only way to achieve liberation. The lesson of “Wrath of the Druids” isn’t to give in to the most benevolent power you can to keep casualties to a minimum. Its lesson is that Eivor should have been fighting for the Druids from the beginning.

Had Eivor and Bárid been fighting for the Druids all along, empowering Ciara and her non-Children of Danu kin rather than fighting at the behest of the High King, perhaps the petty kings would never have called for an inquisition because the Druids would have amassed their own power and influence. Fewer Druids may have been radicalized to the Children’s cause, cultural sites may not have been destroyed, and the defenders of Druid self-determination may not have been left scattered or dead at the end of the conflict. None of this was a guarantee, of course. The unfortunate reality is that liberation simply does not come easy, or else there would be no oppressed peoples. And of course, for Assassin’s Creed, history, much like real life, is set in stone. We can’t change the way the Irish conflicts of the 9th Century played out any more than we can change the histories of so many of the world’s oppressed peoples.

Nevertheless, we must try. We must learn from history, and learn how to accept that it happened; that empathizing with its players is essential and possible to do without justifying their wrongdoings. And if I take one thing away from the entire Assassin’s Creed franchise, especially Valhalla, it’s that no matter the costs, no matter the time it takes, and no matter how deeply complicated the history is, the only true way to achieve liberation for all of the worlds’ peoples is to resist oppression everywhere, understand and empathize with the cyclical history of violence and oppression of every time, and strive for free will and self-determination for everyone.